The Colossus of Nero is not just another ancient statue but a towering 30-meter (98 ft) bronze spectacle. Conceived by Emperor Nero, this monolith stood in the vestibule of his extravagant villa, the Domus Aurea. Spanning multiple hills in Rome, this villa epitomizes imperial luxury.

Wondering why the Roman Colosseum might ring a bell? The nearby Colossus inspired its name. So, sit tight. We’re diving into the story of a crazed emperor’s monument to himself.

Why Did Nero build a statue of Himself?

Nero’s Colossus was more than a decorative piece; it was a strategic display of authority. By erecting this 30-meter-high statue, Nero aimed to both exude unparalleled power and elevate himself to the level of gods.

It was a move to legitimize his rule and instill awe among the masses. Symbolism was extremely important to Roman imperial rule.

The Colossus of Nero May Have Been a Tribute to the Sun God Sol

Contrary to popular belief, the statue might not have been a self-portrait. Some ancient sources suggest it could have been a tribute to the Sun God Sol. This idea blurs the line between Nero’s self-aggrandizement and religious devotion.

The ancient records on this topic are sketchy. While Suetonius claims the Colossus was a statue of Nero, his credibility is often questioned.

Pliny the Elder, another source, reveals that the statue wasn’t even finished during Nero’s rule.

Tacitus, notable for his historical accounts, makes no mention of it.

Political Undercurrents

Remember, Nero wasn’t winning any popularity contests, especially among the Roman elite. He was the last in the line of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and posthumously discrediting him had its benefits.

New emperors, notably Vespasian, and the Flavians would find it convenient to downplay or condemn Nero’s legacy as they established their own reign.

So, whether the Colossus was a godly tribute or a monument to ego remains debatable. But its towering presence left a mark on ancient Rome.

Why was monumental architecture important to the Romans?

In ancient Rome, monumental buildings weren’t just architectural marvels but strategic tools.

Emperors used grand structures to cement their legacy, demonstrate power, and legitimize their rule. These weren’t just buildings but political statements set in stone and marble.

From the Colosseum, a symbol of Roman engineering and cruel spectacles, to the Pantheon, a temple dedicated to all gods, these structures were messages writ large. They served as permanent records of the greatness of their creators and the empire they ruled.

Unifying Culture Through Architecture

But these structures had a broader cultural mission, too. They spread the concept of “Romanness” across the empire. When people saw these monumental buildings, they understood the might, culture, and values that were inherently Roman. The architecture served as a unifying force.

Aligning the emperor with the gods

Like the speculated statue of Sol by Nero, these buildings often had religious undertones. Emperors aimed to bring glory to the gods and, by extension, themselves.

Appearing divine wasn’t just flattering; it was good propaganda. It set the emperor apart, elevating him from a mortal to a god-like figure.

In a nutshell, monumental buildings in ancient Rome were multi-layered in their significance. They were political, cultural, and religious landmarks, each telling a story transcending mere bricks and mortar.

The Death of Nero

Nero’s reign ended in AD 68, kicking off a turbulent period known as the Year of the Four Emperors. This time of rapid power shifts ended with Vespasian seizing the throne. He would go on to make significant changes to the Colossus of Nero.

Vespasian emerged victorious in this chaotic time, taking control of an empire in disarray. His reign would bring about stabilization, and he would make his own mark on Rome’s monumental landscape.

What happened to Nero’s statue?

If we operate under the assumption that the Colossus originally depicted Nero rather than the sun god Sol, then Vespasian promptly modified the statue upon ascending to the throne.

He added a radiate crown and renamed it Colossus Solis. This was in keeping with the Roman tradition of aligning emperors with gods.

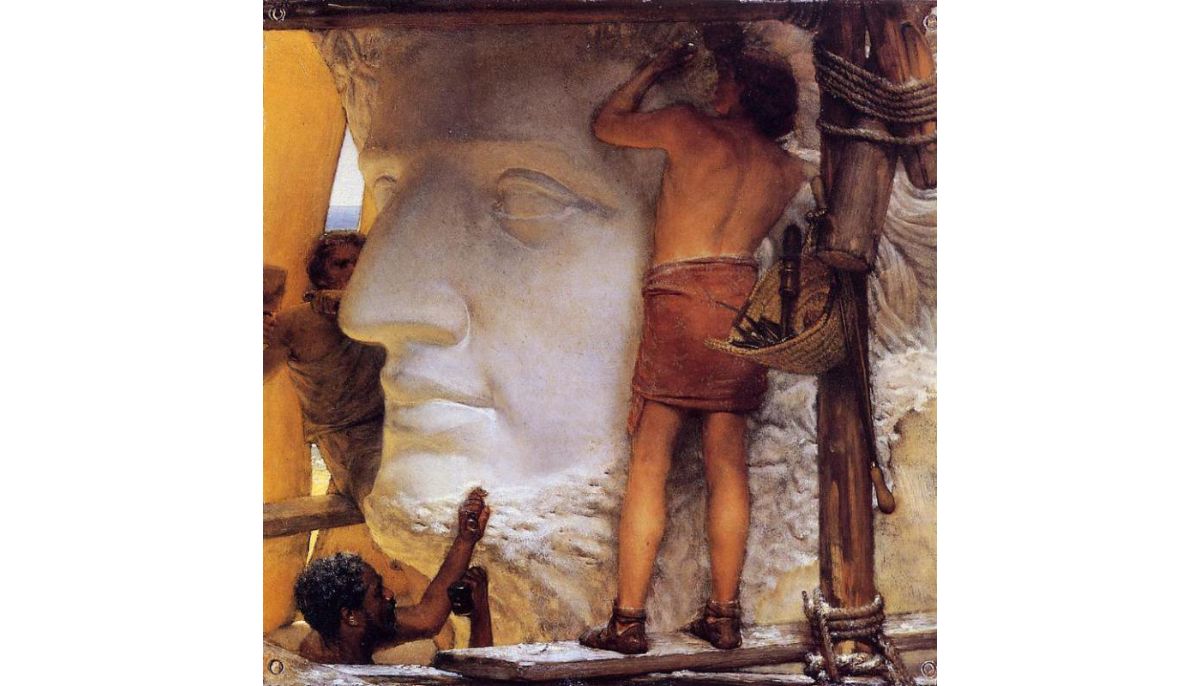

Fast-forward to Emperor Hadrian in around 128 AD. He ordered the Colossus to be relocated just northwest of the Colosseum. The move made space for the Temple of Venus and Roma. Architect Decriannus orchestrated this complex operation, utilizing 24 elephants to do the heavy lifting.

Then came Commodus, the gladiator Emperor. He took the liberty of converting the Colossus into a statue of himself as Hercules simply by replacing the head.

After Commodus’ death, the statue was restored to its prior form as a monument to Sol and remained.

The Destruction of the Colossus of Nero

The likely end of the Colossus of Nero came with the sack of Rome in 410 AD. This cataclysmic event was orchestrated by the Visigoths, led by King Alaric. Rome’s walls were breached, and the city was plundered. The sack weakened the Roman Empire and led to the widespread desecration of its iconic monuments, including the Colossus.

This period also coincided with the ascendancy of Christianity, which often resulted in the destruction of pagan symbols. If the Colossus represented the sun god Sol, it would have been a target for destruction.

The same fate befell other pagan landmarks, notably the tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria. Once a monumental shrine to one of history’s greatest conquerors, Alexander’s tomb suffered from a similar wave of iconoclasm.

Is there anything left of the Colossus of Nero

Today, only the foundations of the pedestal survive as a testament to the Colossus’s once-grand stature and Nero’s lofty ambitions.

The original plinth was largely demolished in 1933 to make way for the construction of Via dell’Impero and Via dei Trionfi. These scant remains are found near the Roman Colosseum and serve as a muted tribute to Rome’s intricate past.

The Colossus of Nero symbolized imperial might, religious alignment, and cultural unity.

It morphed in meaning with each emperor who modified it, reflecting the changing times.

Monuments serve as enduring, though fragmented, pieces of a once-glorious past, now studied to understand better the tides of history and power that shaped the ancient world.