The Byzantine Empire stands as a testament to military ingenuity and strategic prowess. Spanning over a millennium, this Empire’s survival and expansion were significantly influenced by its unique and powerful arsenal.

This article delves into eight key Byzantine Empire weapons that helped create, shape, and protect the realm for a thousand years.

From the renowned Greek Fire to the formidable Theodosian Walls, each weapon symbolizes the Empire’s technological advancements and its enduring legacy in the art of warfare.

1. rhomphaia sword

The Rhomphaia was more than a weapon; it symbolized authority and protection. Carried by the Varangian Guard, these elite guardsmen were often seen with the Rhomphaia on their shoulders, showcasing their role as the Emperor’s protectors.

The Rhomphaia’s design is a topic of debate, with sources unclear on whether it was single- or double-edged. Its size and shape suggest versatility in battle, effective in slashing and thrusting.

The Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard, an elite unit in the Byzantine army, was composed of formidable Viking mercenaries. This guard played a pivotal role in the Empire’s survival through the years, with notable figures like Harold Hardrada among their ranks.

The Varangian Guard was more than just a military unit; it symbolized the Emperor’s power and the Empire’s reach.

Recruiting Vikings, renowned for their combat skills, the guard was a testament to the Byzantine Empire’s ability to integrate diverse warriors into its fold.

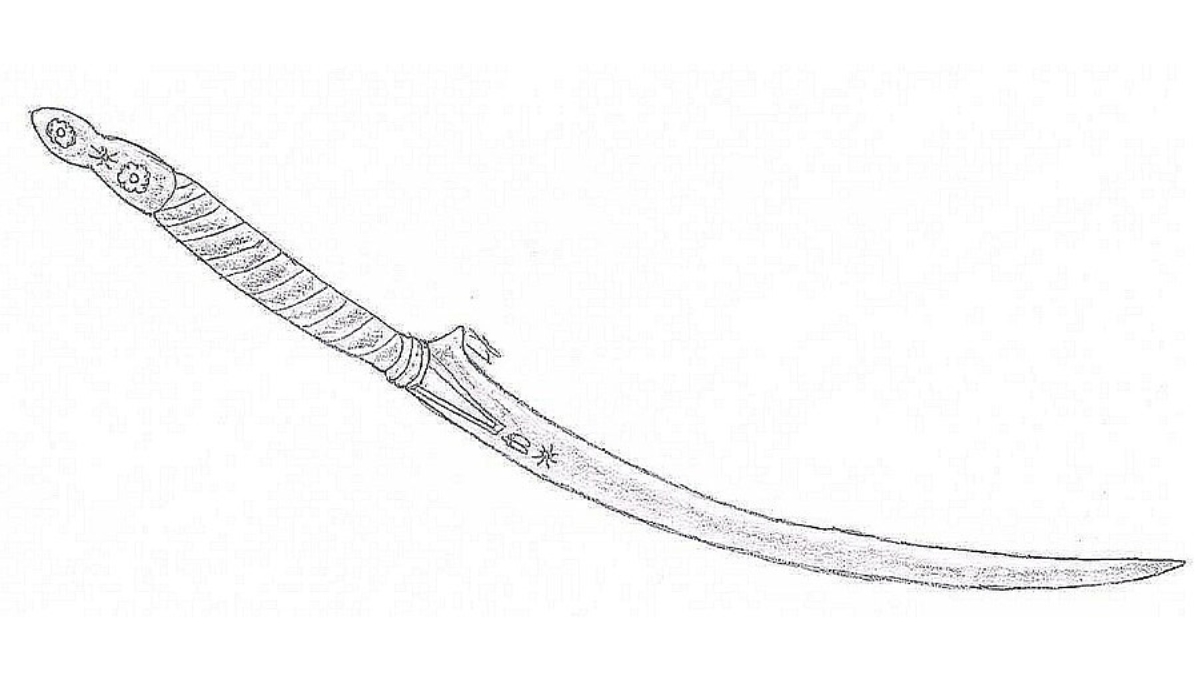

2. paramerion sword

The Paramerion, a saber-like curved sword, was a distinctive weapon in the Byzantine military arsenal, reflecting the Empire’s diverse influences.

Eastern and Steppe Influences

The design of the Paramerion showcases the Byzantine Empire’s ability to assimilate and adapt military technologies from different cultures.

This one-edged cutting weapon, primarily used by Byzantine cavalry, drew inspiration from similar swords of the Middle East. Additionally, scholars suggest a direct influence from the sabers of Turkic steppe peoples like the Pechenegs and Cumans.

These groups, either serving as mercenaries or as part of the Byzantine army, brought their unique weaponry styles, which the Byzantines adeptly integrated into their military practices.

Unique Design and Usage

The Paramerion’s name, meaning ‘by the thigh,’ hints at its unique carrying style. Unlike the traditional straight, double-edged swords suspended by a baldric, the Paramerion was likely worn suspended by slings from a waist-belt.

This method of carrying not only made it easily accessible for cavalry but also distinguished it from other Byzantine weapons.

3. cataphracts – byzantine heavy cavalry

The Byzantine heavy cavalry, particularly the Cataphracts, was not just a military unit but a symbol of the Empire’s might and expansion.

Their high points often coincided with the Empire’s periods of growth and success, especially in confrontations with steppe nomads.

The Terrifying Might of the Cataphracts

Imagine the sight of these heavily armored cavalrymen on the battlefield: a formidable force clad in armor, their horses equally protected, advancing in unison.

The cataphracts were a terrifying presence, their armor clinking and gleaming in the sun, instilling fear in the hearts of their enemies.

Their tactical use of mounted archers to soften enemy lines before a decisive, steady advance made them unstoppable.

Success Against Steppe Nomads

The cataphracts were particularly effective against steppe nomads. These nomadic warriors, known for their mobility and horse archery, were often outmatched by the disciplined, heavily armored Byzantine cavalry.

The cataphracts’ ability to withstand volleys of arrows and close in for hand-to-hand combat gave them a significant advantage. Their success in these encounters protected the Empire’s borders and expanded its influence and control over strategic regions.

Their Role in Byzantine Expansion

The periods of significant use and development of the cataphracts often aligned with the Byzantine Empire’s territorial expansion and consolidation phases.

Under leaders like Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas, the reformed cataphract units were central to military campaigns that pushed the Empire to new heights.

Their presence on the battlefield was critical to the Byzantine military’s ability to outmaneuver and overpower various adversaries.

4. Greek Fire

Greek Fire, a formidable Byzantine invention, remains one of history’s greatest military mysteries. Believed to be based on crude oil or petroleum, possibly from the Black Sea, this incendiary weapon was a crucial factor in the Empire’s naval dominance.

The mere presence of Greek Fire on the battlefield or at sea struck terror into the hearts of the Byzantine Empire’s enemies. Its ability to burn fiercely even on water made it an unparalleled tool in naval engagements.

Greek Fire in Naval Warfare

In naval battles, Greek Fire was a game-changer. Deployed through siphons and flamethrowers, it allowed Byzantine ships to unleash devastating fire attacks on enemy fleets. This technological marvel was instrumental in thwarting the sieges of Constantinople, particularly during the early Arab invasions.

The state Secret recipe

The composition and method of deploying Greek Fire were among the most closely guarded secrets of the Byzantine Empire, known to only a select few. This secrecy added to its effectiveness and contributed to its eventual disappearance.

So well-kept was the secret that, over time, the knowledge of how to make and use Greek Fire was lost. Its use faded from military records, and the recipe vanished, leaving historians and scientists to speculate about its composition and mechanics.

5. Byzantine hand grenades

Following the invention of Greek Fire, the Byzantine Empire continued its tradition of military innovation by developing hand grenades.

These explosive devices emerged around the reign of Leo III (717-741 AD) and saw extensive use during the Crusades and into the Mamluk era.

Design and Functionality

Byzantine grenades were crafted from heavy clay and exhibited a variety of shapes and sizes. Typically, they featured a bulbous or pear-shaped body with a short cylindrical neck. A small aperture at the top was designed for filling and would accommodate a fuse to trigger the explosion.

The average size and presence of a grip on some examples suggest they were designed to be thrown by hand, making them effective in short-range combat.

Usage in Warfare

While primarily used for short-range conflicts, the versatility of Byzantine grenades extended to long-distance battles.

They were likely hurled at enemies using catapults or trebuchets. The grenades could be ignited before release or set alight by fire arrows upon impact, devastatingly affecting enemy forces.

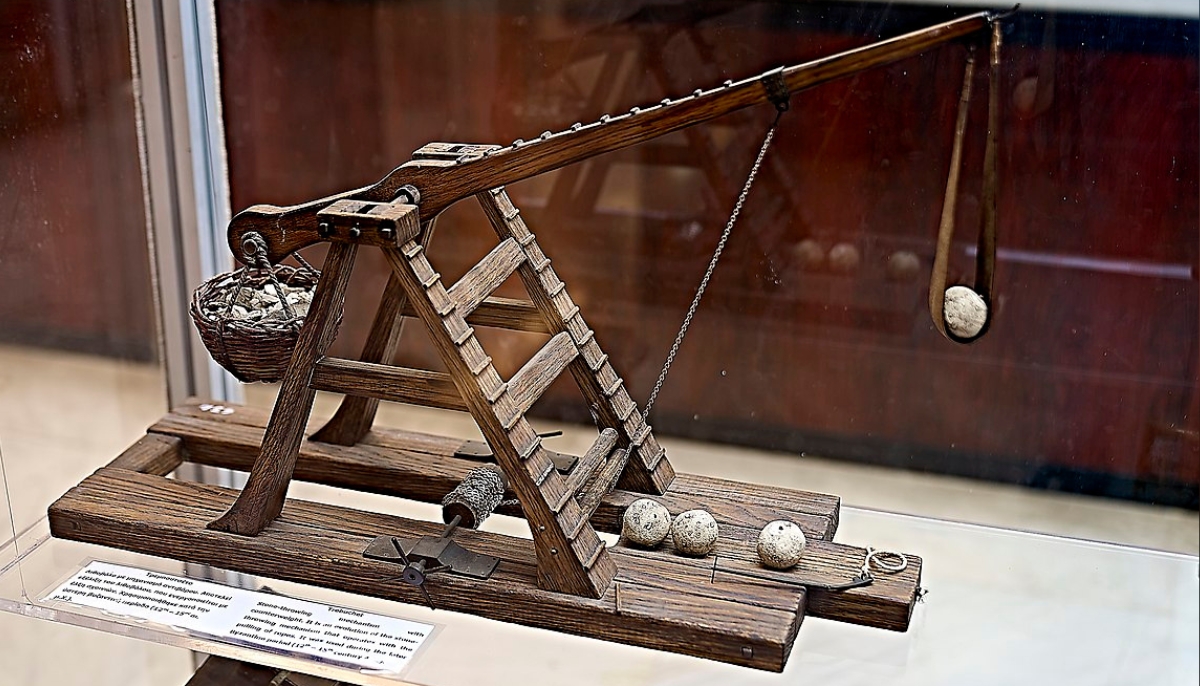

6. Byzantine trebuchets – the city takers

The Byzantine Empire’s military ingenuity is exemplified by their likely invention and use of the traction trebuchet, a powerful siege weapon crucial in medieval warfare.

These “city-takers” were instrumental in the Empire’s ability to capture fortified cities, setting them apart from adversaries like the Turkic nomads.

Development and Description

The military manual Strategikon, attributed to Emperor Maurice, provides early hints of the Byzantine use of siege artillery. It describes wagons transporting artillery crews and equipment, including “revolving ballistae at both ends.”

Initially, this description was thought to refer to torsion or tension weapons like the ballista. However, further analysis suggests it referred to an early form of the trebuchet, a traction-powered siege engine.

The Trebuchet in Byzantine Warfare

By the 10th century, under the guidance of Emperor Leo VI, military manuals like the Tactical Constitutions began to align with contemporary equipment, including the trebuchet, referred to as “Alakatia.”

These were likely pole frame models, easily transportable and quickly assembled, capable of launching stone and incendiary projectiles.

Later in the 10th century, Emperor Nikephoros Phokas emphasized the importance of these siege engines. He ordered that each unit of light infantry should have access to three Alakatia, along with other portable artillery.

This directive highlights the trebuchet’s significance in Byzantine military strategy, particularly in sieges.

Impact on Medieval Siege Warfare

The Byzantine trebuchet was a game-changer in medieval siege warfare. Its ability to hurl large projectiles over great distances with precision made it a feared weapon against fortified cities.

The trebuchet’s effectiveness in breaching walls and towers gave the Byzantines a significant advantage over their enemies.

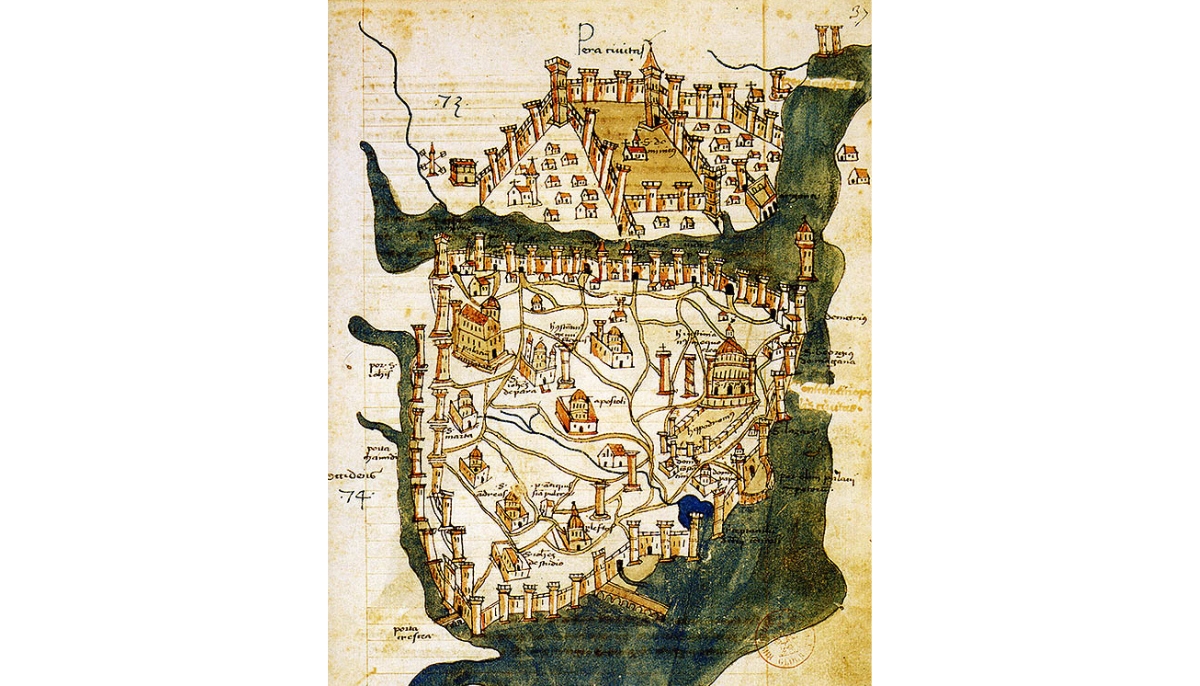

7. golden horn chain

The Great Chain of the Golden Horn was a critical defensive measure for Constantinople, showcasing that not all weapons in an empire’s arsenal need to be offensive. This chain was crucial in protecting the Golden Horn, an essential and strategic waterway for the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Golden Horn and Its Significance

The Golden Horn, an inlet of the Bosphorus in Constantinople, was vital for the city’s defense and commerce.

The Eastern Roman Empire’s naval headquarters were located there, and walls were built along the shoreline to protect against naval attacks. The inlet’s strategic importance made it a focal point for the city’s defense mechanisms.

The Chain’s Function and Construction

At the northern entrance of the Golden Horn, a massive chain was stretched from Constantinople to the Tower of Galata. This chain was a formidable barrier, preventing unwanted ships from entering the inlet.

Historical Challenges to the Chain

The chain’s effectiveness was tested on notable occasions:

- 10th Century – Kievan Rus’ Invasion: The Kievan Rus’ managed to bypass the chain by dragging their longships out of the Bosphorus, around Galata, and relaunching them in the Horn. However, the Byzantines ultimately defeated them, notably using Greek Fire.

- Fourth Crusade – 1204: During this tumultuous period, Venetian ships succeeded in breaking the chain using a ram, a significant event in the Crusade’s history.

- Fall of Constantinople – 1453: Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, unable to break the chain through force, emulated the tactic of the Kievan Rus’. He transported his ships over land around Galata on greased logs, successfully entering the estuary.

The Chain’s Role in Byzantine Defense

The Great Chain of the Golden Horn symbolizes the Byzantine Empire’s ingenuity in defensive strategies. It was not just a physical barrier but a psychological one, representing the Empire’s determination to protect its capital.

While it was eventually circumvented or broken, its presence for centuries as a defensive tool underscores the strategic thinking and resourcefulness of the Byzantine military.

8. Theodosian walls

The Theodosian Walls encircling Constantinople were not just fortifications but a super-weapon in their own right, enabling the city to withstand sieges for over a thousand years.

Initially built by Constantine the Great, these walls were expanded in the 5th century as the city grew, forming a formidable barrier against attacks from both sea and land.

Structure and Design

The walls consisted of an inner and outer wall, separated by a terrace known as the peribolos. The inner wall, the mega teichos (“great wall”), was a solid structure about 4.5-6 meters thick and 12 meters high, faced with limestone and reinforced with brick bands for earthquake resistance. It featured 96 towers of various shapes, providing strategic vantage points and storage.

The Outer Wall

The outer wall, less elaborate but still formidable, was 2 meters thick and up to 9 meters high. It featured arched chambers and a battlemented walkway, with towers positioned to support the inner wall’s towers.

The Moat

A crucial component of the defense system was the moat, over 20 meters wide and up to 10 meters deep, situated about 20 meters from the outer wall.

It featured a crenelated wall and transverse walls, some containing pipes for water supply, serving both as aqueducts and as a means to fill the moat.

Historical Significance

The Theodosian Walls were a testament to Byzantine engineering and military strategy. They saved Constantinople during sieges by various forces, including the Avar–Sassanian coalition, Arabs, Rus’, and Bulgars.

Despite their formidable strength, the Theodosian Walls ultimately fell during the 1453 siege by Ottoman forces.

The advent of gunpowder siege cannons presented a challenge that the walls, for all their resilience, couldn’t withstand indefinitely.

Although they did not readily succumb, and the Byzantines nearly withstood the siege, the walls were eventually breached, leading to the fall of Constantinople.

Preservation and Legacy

Most of the Ottoman period saw the walls largely intact, with dismantling beginning only in the 19th century as the city expanded.

Many parts of the walls still stand today, with restoration efforts ongoing since the 1980s. The Theodosian Walls remain a symbol of the Byzantine Empire’s strength and ingenuity, a super-weapon that protected Constantinople for centuries.