Few emperors have sparked as much debate and fascination as Elagabalus, the teenage ruler whose brief and tumultuous reign from 218 to 222 CE remains a subject of intrigue and controversy.

We begin by tracing the early life and ascent of Elagabalus to the Roman throne, examining his unexpected rise to power and his reign of the Roman Empire during a period of significant transition.

We then focus on three pivotal questions: What were the Religious reforms that proved so controversial? Was Elagabalus transgender? And was Elagabalus a bad emperor?

We will delve into the traditional views on Elagabalus’ gender identity and juxtapose them with modern perspectives, unraveling the layers of his character.

His religious reforms, a subject of controversy, are also scrutinized under a contemporary lens. Furthermore, our assessment of Elagabalus’ leadership and the credibility of historical accounts teases the complexity of his legacy, offering a fresh angle on this intriguing Emperor.

The Early Life of Elagabalus

Born as Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus around 204 AD, the future Roman Emperor Elagabalus grew up in a turbulent period of Roman history. This era was marked by political strife and rapid changes in leadership.

The story of Elagabalus’ rise begins with the assassination of Emperor Caracalla in 217 AD. His successor, Macrinus, faced threats from Caracalla’s family, leading to the exile of Elagabalus and his relatives to Syria.

Was Elagabalus the Son of Caracalla?

While Elagabalus was promoted as the son of Caracalla, this was a strategic fabrication by his grandmother, Julia Maesa, to secure his ascent to the throne. In reality, Elagabalus was not Caracalla’s son; this claim was a political maneuver to leverage the loyalty of those still loyal to Caracalla.

Macrinus’ reign was unstable, and by 218 AD, he was overthrown. Elagabalus, at only 14 years old, was elevated to the throne. The Roman Senate, primarily symbolic and lacking real power, chose to recognize Elagabalus as Caracalla’s son. This decision was more about political expediency than belief in the claim’s truth.

It was a strategic move to legitimize Elagabalus’ rule, reflecting the era’s standard practice of using adoption or claimed familial ties to justify an emperor’s authority.

The Controversial Reign of Elagabalus

Elagabalus’ reign as Emperor began in 218. Before reaching Rome, he spent time in Antioch to address various mutinies, notably quelling revolts led by Gellius Maximus and Verus.

After resolving these conflicts, Elagabalus traveled through Bithynia, Thrace, and Moesia, reaching Italy in the first half of 219. His journey was marked by strategic political maneuvers, including the execution of Macrinus’ supporters.

Political Appointments and Reforms

Early in his rule, he extended amnesty to Rome’s upper class, a strategic move likely influenced by his advisors. However, Elagabalus’ appointments of allies like Comazon to high-ranking positions were perceived as deviations from Roman customs. These decisions began to sow seeds of discontent among the Roman elite.

While Elagabalus held the title of Emperor, it’s evident that the true political power lay with his mother, Julia Soaemias, and especially his grandmother, Julia Maesa. These influential women were key figures in his ascent to the throne and continued to exert significant control over political decisions during his reign.

Personal Interests and Luxurious Lifestyle

Elagabalus’ interests veer towards the opulent aspects of being an emperor. He invested time and resources in enhancing the imperial palace at Horti Spei Veteris. His fascination with circuses and chariot racing was evident in his dedication to these pursuits, often overshadowing his interest in governance.

This inclination towards luxury and entertainment, rather than the day-to-day ruling, suggests that Elagabalus was more a figurehead while his mother and grandmother made the critical decisions.

the Controversial Marriages of Elagabalus

Elagabalus’ marital life began with Julia Cornelia Paula. This union, which seems to have been more traditional, was short-lived. By August 220, Elagabalus had divorced Paula, marking the end of his first matrimonial alliance.

Controversial Union with Julia Aquilia Severa

Elagabalus’ subsequent marriage was far more scandalous. He married Julia Aquilia Severa, a Vestal Virgin. This was a shocking breach of Roman law, as Vestal Virgins were sworn to celibacy.

The marriage was met with public outrage, yet Elagabalus’ disregard for traditional norms continued. He later divorced Severa, only to remarry her later in his reign, further fueling the controversy.

Political Alliance with Annia Aurelia Faustina

His third wife was Annia Aurelia Faustina, a descendant of Marcus Aurelius. This marriage seemed to serve more as a political alliance, linking Elagabalus with a notable Roman lineage.

However, as with his previous marriages, this did not last, and Elagabalus divorced Faustina.

Unconventional Relationships: Hierocles and Zoticus

His relationships with men further complicated Elagabalus’ marital life. Cassius Dio mentions Hierocles, an ex-slave and chariot driver, as another spouse-like figure in Elagabalus’ life.

The Augustan History claims he also married a man called Zoticus, although Dio only refers to Zoticus as his cubicularius, a position usually not associated with marital status.

Elagabalus was not the only gay Roman Emperor.

Fall from Power and Assassination of Elagabalus

Elagabalus’ reign gradually alienated key factions in Rome, particularly the Roman elite and the Praetorian Guard. His policies and lifestyle choices, which often clashed with traditional Roman values, eroded his support base.

Julia Maesa’s Shift in Support

The turning point in Elagabalus’ rule came when his grandmother, Julia Maesa, assessed the situation and decided to withdraw her support. Recognizing the growing discontent with Elagabalus’ reign and foreseeing its potential consequences, she shifted her allegiance to her other grandson, Severus Alexander.

Political Maneuvering and Assassination Attempts

Sensing the change in dynamics and the threat posed by Alexander, Elagabalus engaged in a series of desperate political maneuvers to maintain his power.

He attempted several times to assassinate Alexander, but these attempts were unsuccessful. Elagabalus’ tactics only exacerbated the situation, leading to further instability and loss of support.

Rumors and Revolt

Elagabalus’ final act in this political drama involved spreading rumors about Alexander’s health, possibly to gauge the reaction of the Praetorian Guard and assess his cousin’s support among them.

This move, however, backfired spectacularly. The Praetorian Guard, already disenchanted with Elagabalus, saw this as a final straw. They revolted against Elagabalus, declaring Alexander as the new Emperor.

The Violent End of Elagabalus’ Reign

The revolt by the Praetorian Guard led to the brutal assassination of Elagabalus and his mother, Julia Soaemias, in 222. This violent and abrupt end marked the culmination of a reign filled with controversy and unconventional rule.

Elagabalus’ Religion – Devotion to the Sun God Elagabal

Roman religion in Elagabalus’ time was a complex mix of polytheism, with diverse deities revered across various regions. This regional variety meant that, despite a common religious framework, practices and beliefs varied significantly.

Elagabalus was devoted to the Syrian Sun God Elagabal, a deity unique to his region and culture. His family’s hereditary rights to the priesthood of Elagabal in Emesa (modern Homs), within the Arab Emesene dynasty, underscored the localized nature of religious practices in the Roman Empire.

Elagabalus’ devotion to the Syrian Sun God, Elagabal, starkly contrasted with the religious preferences of the more conservative Roman senators, who typically followed gods like Apollo. This difference in religious beliefs would be exploited by his opponents in Rome.

While some emperors might have tried to bridge these religious divides, Elagabalus’ approach leaned more towards imposing his religious beliefs, likely exacerbating tensions with the Roman elite.

Religious Reforms of Emperor Elagabalus

One of the most significant religious reforms initiated by Emperor Elagabalus was the elevation of the sun god Elagabal to the highest position in the Roman pantheon.

Around the end of 220, possibly coinciding with the winter solstice, Elagabalus declared Elagabal the supreme deity. This move shifted from traditional Roman religious practices, as it placed a foreign god above Jupiter, the king of the Roman gods.

Elagabalus assumed the title “sacerdos amplissimus dei invicti Soli Elagabali,” which translates to “highest priest of the unconquered sun god Elagabal.”

Efforts to Integrate Elagabal with Roman Religion

To blend this new religious focus with established Roman practices, Elagabalus proposed a union of Elagabal with traditional Roman goddesses like Astarte, Minerva, or Urania.

This syncretism was aimed at creating a bridge between the old and the new, suggesting a possible effort to form a new Capitoline Triad with Elagabal, Urania, and Athena, replacing the traditional triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

Controversial Marriage to a Vestal Virgin

Furthering his religious agenda, Elagabalus caused a scandal by marrying Aquilia Severa, a Vestal Virgin and high priestess of Vesta.

He justified this unprecedented act by claiming their union would produce divine offspring. This action not only violated Roman law but also deeply offended traditional religious sensibilities, as Vestal Virgins were sworn to celibacy under penalty of death.

Construction of the Elagabalium

Elagabalus commissioned the construction of a grand temple, the Elagabalium, on the Palatine Hill, dedicated to housing the deity Elagabal.

The god was represented by a unique black meteorite from Emesa, revered as a divine symbol. This temple became the center of Elagabalus’ religious reforms and practices.

Personal Piety and Public Rituals

To demonstrate his devotion, Elagabalus underwent circumcision and vowed to abstain from pork, aligning himself more closely with the religious customs associated with Elagabal. He engaged in elaborate rituals, including dancing around the altar of Elagabal to the rhythm of drums and cymbals, a spectacle that he insisted the Roman senators witness.

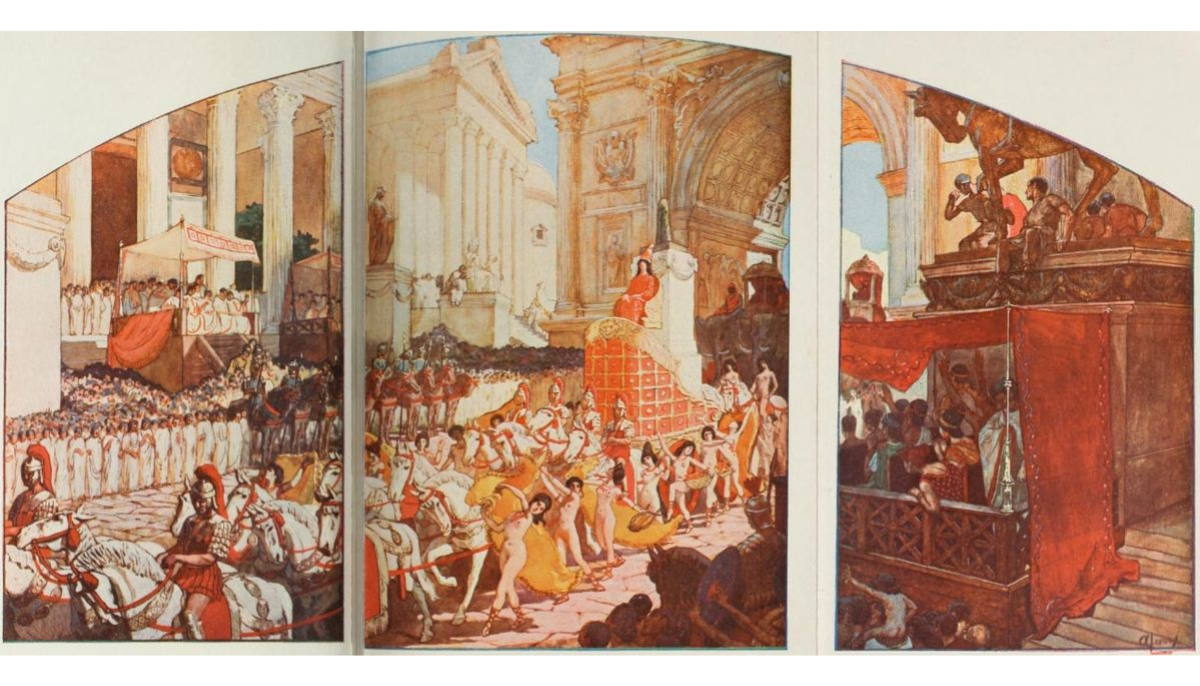

Elagabalus also instituted a major festival each summer solstice, celebrating Elagabal with grand processions. A notable feature was a parade where the god’s stone was carried through Rome on a six-horse chariot, with Elagabalus running backward in front of it, symbolizing his subservience and reverence to the deity.

In a bold move, Elagabalus transferred many sacred Roman relics to the Elagabalium, including the emblem of the Great Mother, the eternal fire of Vesta, the Shields of the Salii, and the Palladium.

Legacy of Elagabalus’ Religious Reforms

While Elagabalus’ religious reforms were radical and met with ridicule and resistance from many contemporaries, his focus on sun worship did find resonance among some, particularly soldiers.

His promotion of Elagabal as a central deity was a precursor to the later widespread worship of Sol Invictus among Roman soldiers and several subsequent emperors.

Was Elagabalus a Transgender Emperor?

Following Elagabalus’ religious practices, it’s essential to consider another aspect of his life that became a target for his enemies: his gender identity.

Similar to his unconventional religious views, Elagabalus’ gender expression was far from the norms of Roman society, providing fertile ground for his adversaries to exploit.

Historical Bias and Interpretation

Elagabalus’ portrayal by Roman sources is often clouded with negativity as he was not viewed as a successful ruler.

Roman chroniclers commonly used moral judgments to discredit those they opposed. Given this, it’s likely that the accounts of Elagabalus were exaggerated to paint him in a worse light.

Cultural Perceptions and Eastern Influence

Rome often stereotyped Eastern cultures as effeminate and decadent. These biases might have influenced how Elagabalus was depicted with his Eastern roots and atypical behavior. His actions, which were seen as unconventional, could have been exaggerated to fit this narrative of Eastern ‘softness.’

Elagabalus’ Gender Expression: In Dio’s Words

Historical accounts, particularly those by the Roman historian Cassius Dio, shed light on Elagabalus’ unconventional gender expression and relationships. Dio’s descriptions are pretty explicit and give us a glimpse into how Elagabalus was perceived in his time.

Dio states that Elagabalus played the role of a wife to Hierocles, a chariot driver from Caria, indicating a relationship that defied traditional gender roles. He writes, “Elagabalus delighted in being called Hierocles’s mistress, wife, and queen.”

Further emphasizing Elagabalus’ preference for men, Dio mentions his marriage to Zoticus, an athlete from Smyrna. While Dio does not explicitly call Zoticus his husband, he mentions that Zoticus was his cubicularius, a term that implies an intimate relationship.

Dio also provides a vivid account of Elagabalus’ behavior in public spaces, stating, “Elagabalus prostituted himself in taverns and brothels.”

Most strikingly, Dio recounts Elagabalus’ desire to alter his body, reflecting a deep-seated wish to align his physical form with his gender identity. He notes, “The emperor reportedly wore makeup and wigs, preferred to be called a lady and not a lord, and supposedly offered vast sums to any physician who could provide him with a vagina by means of incision.”

These quotes from Dio paint a picture of an emperor who not only challenged the gender norms of his time but also actively sought to redefine his own identity in a society that was not ready for such changes.

Modern Interpretations of Elagabalus’ gender

In light of the detailed accounts by historians like Dio, it’s conceivable that by today’s standards, Elagabalus could be considered transgender. Dio’s vivid descriptions of Elagabalus’s behavior and preferences suggest a profound divergence from the gender norms of his time.

However, applying modern gender definitions to historical figures like Elagabalus is complex. The concept of being transgender, as understood today, did not exist in Roman times. Our current understanding of gender identity is shaped by cultural, social, and scientific advancements that were not present in ancient Rome.

Therefore, while the accounts point towards behaviors and desires that align with modern interpretations of transgender identity, caution is necessary when retrofitting contemporary terms to historical figures.

If there was a Roman who could fit the modern understanding of being transgender, Elagabalus would be a likely candidate. His life story, as told through historical sources, albeit with a degree of bias and uncertainty, presents a narrative of a person who consistently defied and redefined the gender norms of his era.

Was Elagabalus a Bad Emperor?

Cassius Dio, a senator and historian who lived during Elagabalus’ time, provides a detailed account of his reign. However, Dio’s position within Severus Alexander’s government, Elagabalus’ successor, likely colored his depiction.

He often compares Elagabalus to Sardanapalus, a figure notorious for a decadent lifestyle, indicating a bias in his writings. Herodian, another contemporary, provides an overlapping yet less detailed account focusing more on Elagabalus’ religious reforms.

The Augustan History, written much later, contributes significantly to Elagabalus’ notorious image. This source, filled with scandalous and sometimes dubious claims, has been both influential and controversial in shaping the historical view of Elagabalus.

Modern Historians’ Reassessment

In recent times, historians like Martijn Icks and Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado have questioned the reliability of these ancient sources.

They argue that Elagabalus’ downfall was more a result of political power struggles and his unorthodox religious policies than his personal vices.

Despite varying interpretations, it’s generally agreed that Elagabalus was more focused on personal interests, particularly religion than effective governance.

His rule was marked by a lack of interest in the administrative and military aspects of leadership, making him a largely ineffectual emperor.

Comparison with Other Emperors

Even though he is remembered as one of Rome’s craziest Emperors, Elagabalus was likely not as damaging as emperors like Nero, Caligula, or Honorius. His reign did not result in significant long-term harm to the empire.

The focus on his moral and personal life, likely exaggerated by his contemporaries and later historians, overshadows other aspects of his rule.