Few spectacles capture the imagination quite like the gladiator games of Ancient Rome. These events, more than just bloodsport, were a mix of cultural significance, political power play, and public fascination.

From the sands of the Colosseum to the heart of Roman life, gladiators held a mirror to the society of their time. This article delves into the world of these fabled warriors, exploring their origins, the variety of their weapons, and the gradual decline of their role in Roman society.

The origins of gladiators in ancient Rome

The origin of gladiator fights in Ancient Rome is not precisely known, but historians believe they began around the 3rd century BC. The historian Livy noted this period as a possible starting point.

Evidence of gladiator fights is seen in a 4th-century BC Campanian fresco. Moreover, there are indications that the Etruscans, who lived in Italy before the Romans, may have had similar practices as early as the 8th century BC. These might have been influenced by Greek colonists.

Gladiator fights likely evolved from funeral rites. Early Romans believed that the souls of the dead needed blood to be appeased. Initially, these fights might have been part of these rites, growing into a form of public spectacle over time.

As Rome expanded, gladiator fights became more elaborate and popular. They were no longer just funeral rites but a form of entertainment for the Roman people.

The different types of gladiator

In ancient Rome, a diverse array of gladiator types emerged, many of whom were initially prisoners of war.

Each type of gladiator specialized in distinct weapons and fighting techniques, adding variety and excitement to the gladiatorial games.

- Andabata: A blindfolded gladiator, sometimes associated with chariot fighters like essedarii.

- Arbelas: A gladiator type mentioned in dream interpretation texts, possibly named after a cobbler’s tool.

- Bestiarius: A beast-fighter, often involved in battles against animals.

- Bustuarius: A “tomb fighter,” associated with funeral games and considered low in the gladiator hierarchy.

- Cestus: A fist-fighter or boxer armed with a heavy-duty knuckleduster-like weapon.

- Crupellarius: Heavily armored Gaulish fighters, described by Tacitus as slow and cumbersome.

- Dimachaerus: A gladiator who wielded a sword in each hand.

- Eques: A horseman or cavalryman-type gladiator, initially lightly armed but later more heavily equipped.

- Essedarius: A chariot fighter, possibly fighting on foot or from the chariot.

- Gallus: A “Gaul” gladiator, heavily armored, later evolved into or replaced by the murmillo.

- Gladiatrix: A rare female gladiator, existing towards the end of the Roman Republic.

- Hoplomachus: Armed similarly to a Greek hoplite, fought against myrmillones or Thraeces.

- Laquearius: Possibly a type of retiarius, using a lasso instead of a net.

- Murmillo: Heavily armored, often fighting Thraex or hoplomachus, identifiable by a fish-crest helmet.

- Parmularius: Gladiators who carried a small shield, often equipped with two greaves.

- Provocator: Mirrored legionary equipment, only fought against other provocatores.

- Retiarius: A “net fighter,” armed with a trident and net, often without a helmet.

- Rudiarius: A freed gladiator, often continuing to fight or serve in other capacities in the ludus.

- Sagittarius: An archer, not frequently mentioned in historical sources.

- Samnite: An early type of heavily armed fighter, named after the Samnite people.

- Scissor: Used a unique weapon resembling a pair of open scissors.

- Scutarius: Any gladiator who used a large shield (scutum).

- Secutor: Designed to fight the retiarius, with a smooth, round helmet.

- Thraex: Wore protective armor similar to the hoplomachus and used a curved Thracian sword.

- Veles: Mentioned rarely, presumed to have fought on foot with a spear, sword, and small shield.

The armor and weapons of gladiators

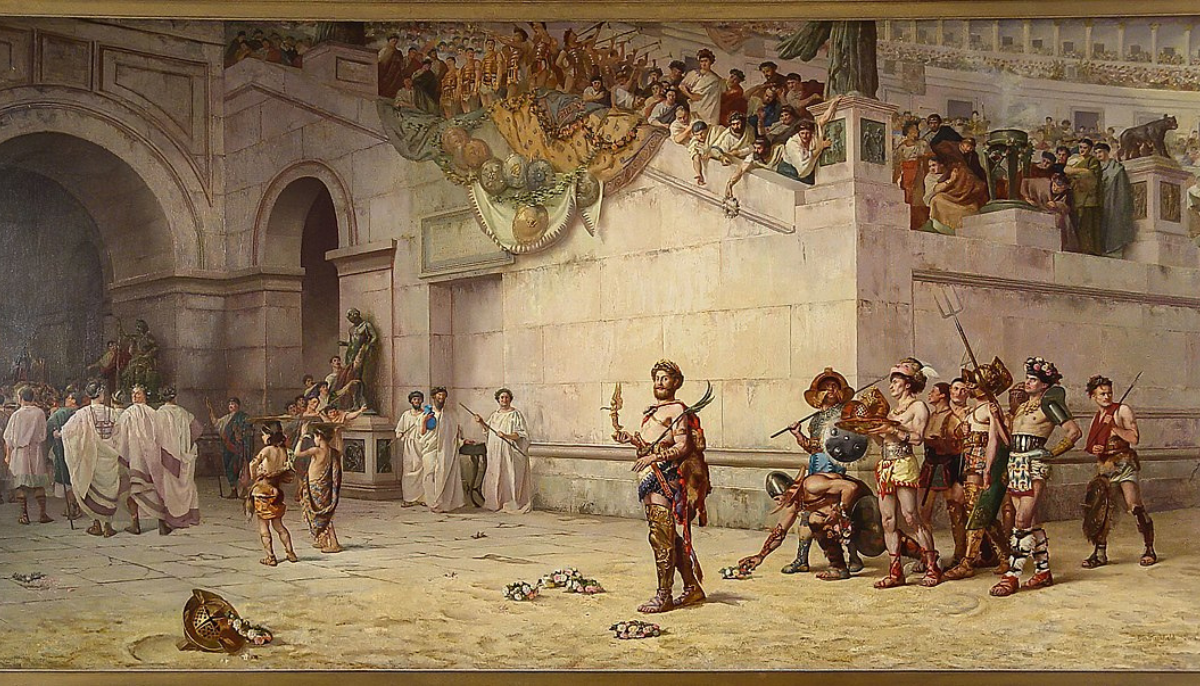

The armor and weapons of gladiators in Ancient Rome were diverse and often symbolized the enemies of Rome. Initially, many gladiators were prisoners-of-war, like Gauls, Samnites, and Thraeces (Thracians), who used their native weapons and armor. This diversity in equipment was a hallmark of gladiatorial combat, with different types specializing in specific weapons and fighting styles.

Gladiators were usually armed differently to ensure balanced and fair contests. Combatants typically faced opponents with different but equivalent equipment. Most fights occurred between gladiators from the same school or ludus, although occasionally, specific gladiators were requested to fight those from another ludus.

The equipment of gladiators served not only practical combat purposes but also played a role in spectacle and showmanship. Elite gladiators donned high-quality, decorative armor for the pre-game parade (Pompa). Notable examples include Julius Caesar’s gladiators, who wore silver armor, Domitian’s in golden armor, and Nero’s adorned with carved amber. Their attire was often luxurious, with peacock feathers for plumes and tunics or loincloths featuring gold thread patterns.

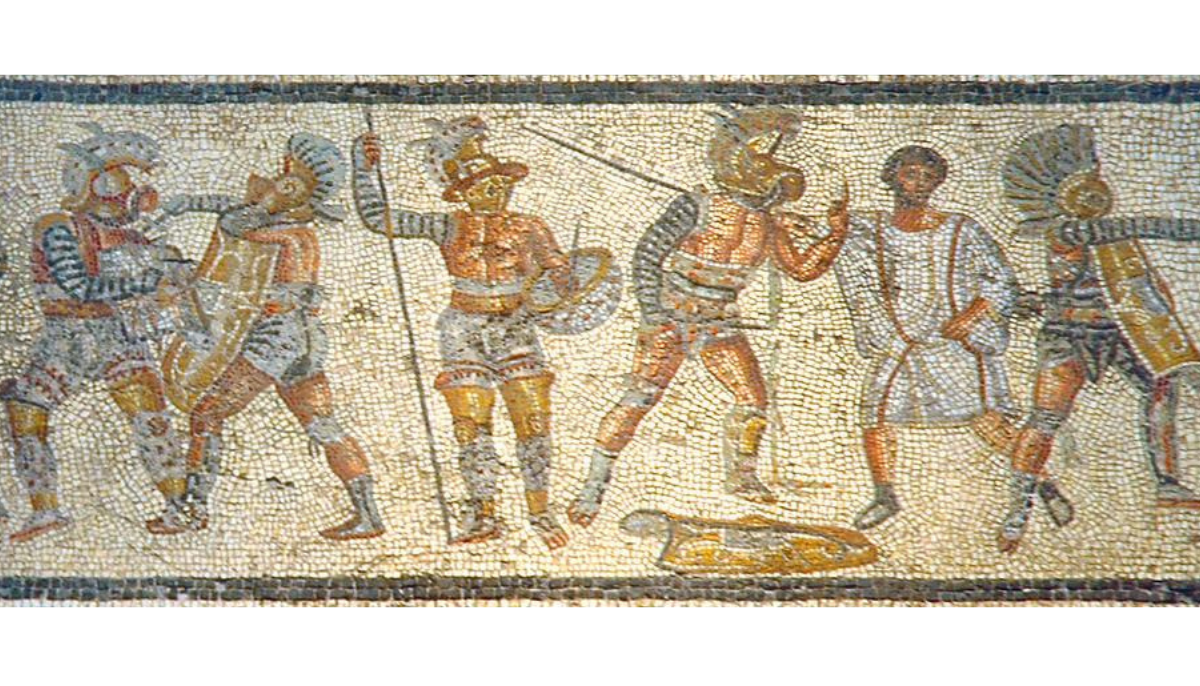

For actual combat, gladiators used functional and sometimes elaborately decorated armor. Artistic depictions, such as reliefs and mosaics, often show gladiators with various tassels hanging from an arm or leg, speculated to be a form of “scorecard” indicating the number of fights a gladiator had won.

The contests themselves were managed by arena referees and fought under strict rules and etiquette. This structured approach ensured that the battles were not only entertaining but also maintained a level of fairness and skill, emphasizing the prowess and training of the gladiators.

were gladiators always slaves?

Gladiators in Ancient Rome were primarily slaves. They were often prisoners of war, criminals, or slaves bought specifically for the purpose of gladiatorial combat. Their lives were not their own; they were owned by their masters and trained rigorously for the brutal games.

However, not all gladiators were slaves. There were also volunteers attracted by the glory, fame, and potential financial rewards. These free men, often from lower social classes, willingly chose the life of a gladiator. For them, the arena offered a chance to elevate their status and earn significant sums of money.

The world of gladiators was also a lucrative business for trainers. Known as ‘lanista,’ these individuals trained gladiators in special schools. These schools were akin to a blend of barracks and prisons, where gladiators lived, trained, and were kept under strict control. The success of a lanista depended on the performance of his gladiators, making it a highly competitive and profitable business.

Did gladiators fight with animals?

Gladiators also occasionally fought wild animals. However, this was more the domain of venatores, specialists in hunting and battling animals.

These warriors, while not typically identified as gladiators, displayed immense bravery. They faced dangerous animals like lions, bears, tigers, bulls, boars, dogs, cheetahs, panthers, rhinoceroses, and hyenas.

These animal fights were hugely popular in Ancient Rome. Although not technically gladiator battles, they were a staple in large events at amphitheaters across the empire. The perilous nature of these contests added a unique thrill to the public spectacles.

Bestiarii were not trained fighters or animal experts but rather criminals or prisoners of war forced to battle animals. Often, many bestiarii were released into the arena simultaneously with a host of wild animals, leaving them with little chance of survival.

There is a grim account of one lion killing about 200 bestiarii in a single event. These instances were less about fair competition and more about punishment or providing a gruesome form of entertainment for the Roman audiences.

Did gladiators always die in battle?

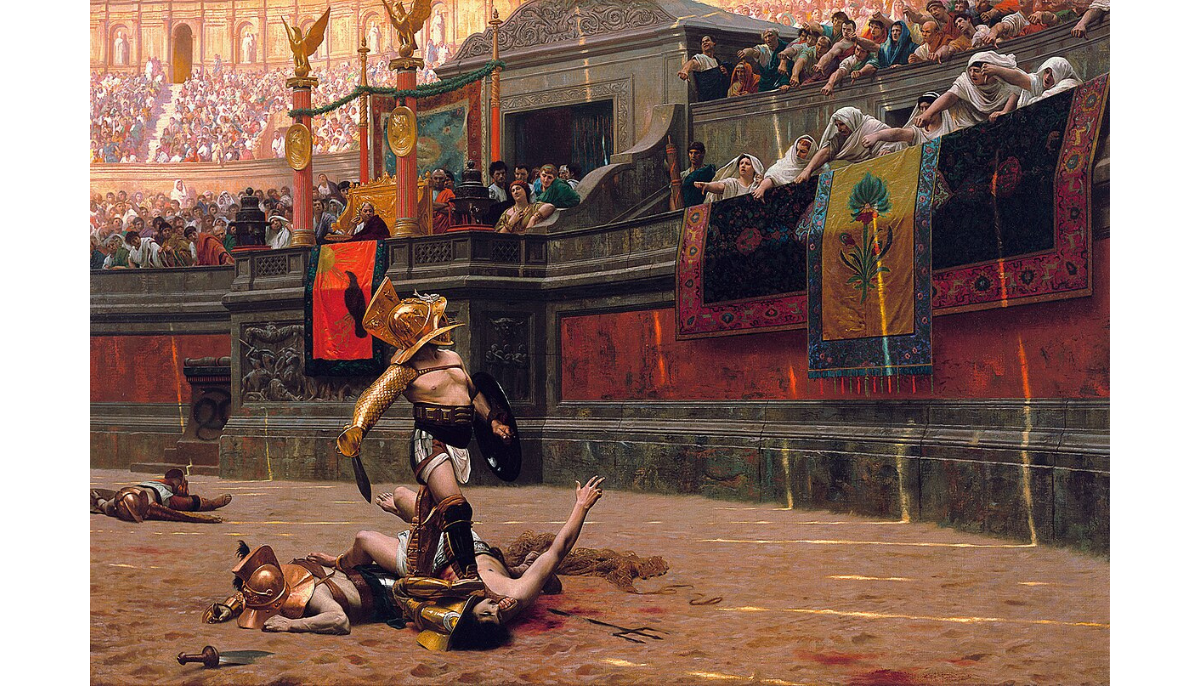

The fate of gladiators in Ancient Rome varied, and they did not always die in battle. While the term “gladiator” encompasses various types of fighters, the traditional man-vs-man gladiator battles had a lower mortality rate than often perceived.

Historical estimates suggest that only about 10 to 20% of these battles ended in death. This is evidenced by surviving graffiti in Pompeii, which served a purpose similar to modern boxing promo posters. These inscriptions often showed fighters’ records and previous victories, indicating that many gladiators survived multiple battles.

However, it’s important to differentiate between professional gladiator fights and gladiatorial games used as a form of punishment. In the latter case, such as with criminals or prisoners of war, these games were indeed a method of execution. The individuals forced into these battles, often with little or no training, faced almost certain death.

Why were gladiator games popular in ancient Rome?

Gladiator games in Ancient Rome were a form of entertainment that evolved significantly over time. Initially, they may have started as funeral rites. The historian Livy mentions that in 264 BC, three pairs of gladiators fought to honor the deceased father of Junius Brutus Pera. As Rome expanded, so did the scale of these games. By 183 BC, records mention a combat involving 120 gladiators to honor Publius Licinius.

The first major state-sponsored event was in 105 BC when consuls presented gladiator combat as part of a military training program. The gladiators, brought from Capua, showcased what was termed “barbarian combat.” This event marked a significant shift, making gladiator games a popular public spectacle.

The political power of gladiators

The concept of gladiator games quickly spread to Roman provinces, indicating the empire-wide appeal of these spectacles. They also became a potent political tool. In the late Republic, wealthy politicians would host games to gain public favor, especially around elections. Julius Caesar, for instance, famously held games featuring 320 pairs of gladiators in silver armor.

Emperor Augustus later imposed limitations on private games, linking large public spectacles to the growing imperial cult. This connection between entertainment and politics was further solidified under his rule.

Gladiator games eventually became a defining element of the Roman concept of “bread and circuses” – entertainments used to keep the public content and showcase Roman power. They often included historic reenactments. For instance, an emperor might reenact a significant military victory, using the games to highlight his achievements, wealth, and power.

The peak of these spectacles was during Emperor Trajan’s reign. Between 108 and 109 AD, he celebrated his Dacian victories with an extravagant event involving 10,000 gladiators and 11,000 animals over 123 days. This not only demonstrated the might of Rome but also served as a form of mass entertainment, blending spectacle, politics, and public appeasement.

The decline of the gladiator

The popularity of gladiator games in Ancient Rome began to wane due to a combination of economic and religious factors. As the empire entered a period of crisis in the 3rd century, the extravagant costs of organizing these events became increasingly burdensome. Funding such lavish spectacles in an economically strained environment proved difficult.

Simultaneously, the growth of Christianity played a pivotal role in the decline of gladiator games. Christians, who were becoming more influential in Roman society, generally disapproved of these violent spectacles. Their reluctance to attend such events gradually diminished the games’ audience base.

In 315, Emperor Constantine the Great took a significant step by condemning the practice of using child-snatchers in arena games. A decade later, he further forbade criminals from being forced to fight to the death as gladiators. This shift in policy marked a crucial change in the Roman attitude towards gladiatorial combat.

Emperor Theodosius I, ruling from 379 to 395, adopted Nicene Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire. He banned pagan festivals, and while the ludi (public games) continued, they gradually lost their pagan elements, including gladiator fights.

the last fight in the Colosseum – the final gladiator fight

The last recorded gladiator fight in the Colosseum remains unknown, but the practice legally ended in the Western Roman Empire under Emperor Honorius. In 399 and again in 404, he issued bans on gladiator games, reportedly influenced by the martyrdom of Saint Telemachus, a Christian monk killed by spectators at a gladiator event.

Even though the bans were repeated, venationes (animal hunts) continued beyond 536. By this time, however, the public’s interest in gladiator contests had significantly declined throughout the Roman world. In the Byzantine Empire, which succeeded the Eastern Roman Empire, theatrical shows and chariot races became the primary forms of entertainment, often receiving generous imperial subsidies.

The diverse types of gladiators, each with their unique fighting styles and equipment, added to the richness and excitement of these games. Could bullfighters, with their blend of danger, skill, and public display, be considered the closest contemporary equivalent to Roman gladiators?