The search for Alexander the Great’s missing body has been one of the most captivating mysteries in history. Historians have scoured the globe for any trace of the legendary conqueror’s final resting place for over a thousand years.

However, a new and seemingly outlandish theory has emerged that suggests the answer has been hiding in plain sight. Recent analysis indicates that Alexander may have been buried in St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice, sparking renewed interest in this enduring mystery

What we know about Alexander’s final resting place

Alexander the Great’s tomb was initially in Babylon before being moved to Alexandria, Egypt. The site was a symbol for the Ptolemaic dynasty and attracted Roman leaders like Julius Caesar and Augustus.

However, the tomb’s location was eventually lost. Some speculate it was destroyed in the fourth century or during the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the seventh century.

Alexander the God

During his life, Alexander cultivated a semi-divine status. He claimed lineage from Achilles and Heracles, which was confirmed by the oracle at Delphi. This divine status was acknowledged by the Macedonians, Ptolemies, and Romans, further legitimizing their rule.

The rise of Christianity in the fourth century impacted the veneration of Alexander. Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the empire’s sole religion, leading to the persecution of pagans and possibly contributing to the tomb’s disappearance.

Today, the tomb’s location remains a mystery, prompting various theories. Some even suggest that Alexander’s body may have been moved to Venice. Read on to explore this intriguing possibility.

Was Alexander the Great Disguised as Saint Mark?

British historian Andrew Chugg first proposed the mistaken identity theory. In 2004 he made the case that the mummified remains of St. Mark were that of Alexander the Great.

Who Was Saint Mark?

Mark the Evangelist was a prominent Christian preacher in the first century, credited as the author of the Gospel of Mark and for establishing the first Christian church in Africa. He met his martyrdom in Alexandria in 68 AD at the hands of pagans.

Surprisingly, there is no mention of the whereabouts of St. Mark’s body for over 300 years in the historical record. According to multiple Christian sources, it is believed that the pagans burnt his body at his execution.

The first mention of a tomb of Saint Mark appears in records from the late fourth century, coinciding with the period when the body of Alexander the Great went missing.

The Story of the Body of St. Mark

For three centuries, the body rested peacefully, its identity as a Christian saint shielding it from harm.

But as the 7th century waned, a new religious tide swept North Africa, casting a shadow over the corpse’s sanctuary.

In 641 AD, Muslim armies captured Alexandria from the Byzantine Empire, transforming churches into mosques and endangering Christian religious sites.

The body, whether that of Alexander the Great or Saint Mark, was suddenly in peril.

A Daring Rescue in Alexandria

In 828 AD, a sense of urgency filled the air in Alexandria as Christian sites faced escalating threats. That year, a group of Venetian merchants arrived in the city.

During their visit, they paid their respects at the church dedicated to St. Mark. There, a worried local priest confided in them, saying the church and its sacred relics stood on the brink of destruction.

Inspired to act, the merchants and local Christians concocted an audacious plan to smuggle the body out of Alexandria and toward safety in Venice.

Employing cunning, they placed the sacred corpse onto a cart and concealed it beneath a layer of pork—knowing this would discourage close inspection by Muslim authorities.

Their ruse worked. They sailed unimpeded back to Venice, where the body was initially interred in the Ducal Palace.

A Final Resting Place

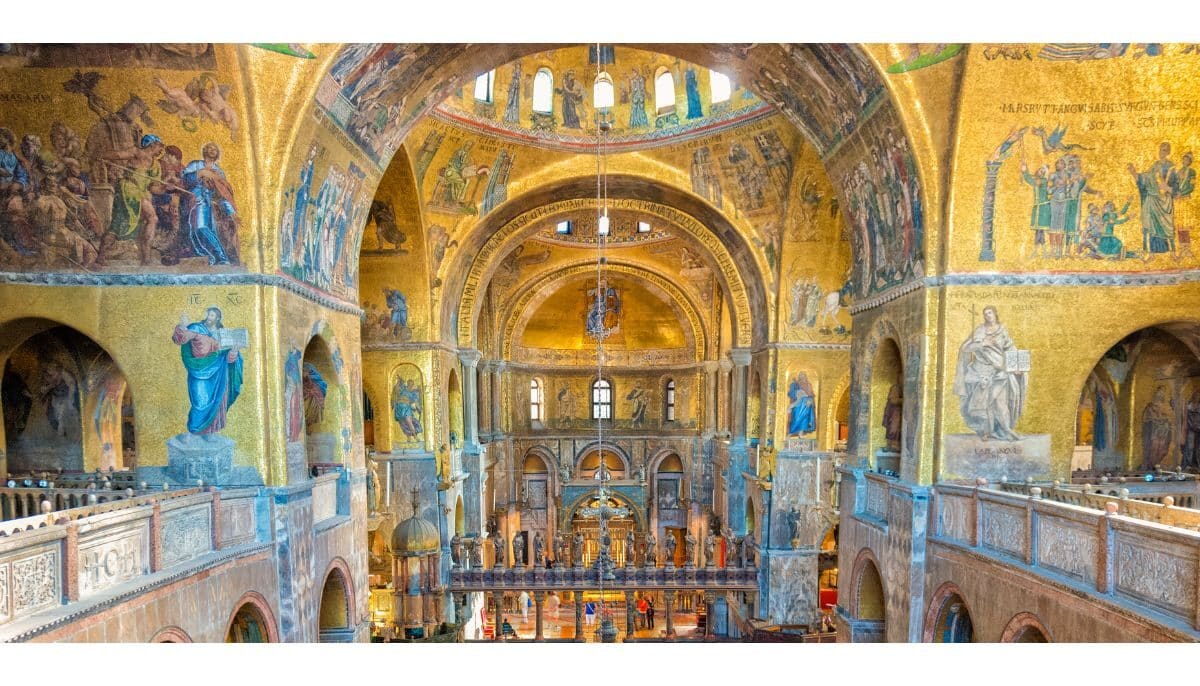

In 1063 AD, the body was moved one final time. It was laid to rest in the newly constructed Basilica San Marco, a magnificent edifice built specifically to house this revered relic.

Whether it’s the final resting place of Alexander the Great or Saint Mark, the tomb is a silent witness to centuries of religious and political turmoil, its secrets locked away in the heart of Venice.

Verdict: Is Alexander the Great Buried in St Mark’s Cathedral?

The theory that Alexander the Great’s body is interred in St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice has garnered attention for its compelling evidence.

While not definitive, these factors add layers of intrigue to the hypothesis. Here’s a closer look at the evidence supporting this captivating claim.

The Gap in Historical Records

One of the most compelling aspects of the theory that Alexander the Great is buried in St. Mark’s Cathedral is the mysterious gap in historical records about St. Mark’s body.

There is no mention of the body for several centuries, raising important questions about its true identity. This lack of historical tracking is uncharacteristic for such an important religious relic.

Mummification Anomaly

Another intriguing detail is that the body of St. Mark is mummified. According to Christian burial practices, mummification should never have occurred. Pagan sources at the time stated the body had been burnt.

However, mummification was common in ancient Egypt, where Alexander died, offering a point of connection between the body and the Macedonian conqueror.

Violent Transition in Alexandria

Alexandria, where the body was originally interred, underwent a violent transition towards Christianity.

In this city, local religions and sects were deeply ingrained, more so than in other parts of the Roman Empire. This cultural setting increases the likelihood that locals would take measures to protect Alexander’s body, given its immense cultural value.

Artistic Similarities

The limestone block in the crypt of the Basilica San Marco offers another tantalizing clue. This block features carvings of a sword and spear, symbols closely associated with the Macedonian dynasty.

Moreover, the shield on the block bears a star strikingly similar to one found in the tomb of Philip II, Alexander’s father. These artistic similarities provide a visual link between the body in the Basilica and Alexander the Great.

Andrew Chugg’s Theory on Stone Size

Researcher Andrew Chugg has made an important contribution to this theory. He discovered that the carved stone in the Basilica is an exact fit for the top of Nectanebo II’s sarcophagus, found in Memphis, Egypt.

Nectanebo II was initially thought to be the occupant of this sarcophagus. Chugg suggests that Alexander could have been initially interred here while Ptolemy I constructed his final tomb, making the stone a crucial piece of evidence.

No DNA or Visual Analysis

Adding to the theory’s allure is the fact that no DNA or visual analysis has been conducted on the mummified corpse. The Catholic Church has prohibited any such tests, considering them a form of desecration. This lack of concrete evidence keeps the theory in the realm of plausible speculation.

While the theory that Alexander the Great’s body is buried in St. Mark’s Cathedral is not conclusively proven, the pieces of evidence available make for a compelling case.

From gaps in historical records to artistic links with the Macedonian dynasty, the clues are intriguing and warrant further investigation.

Verdict: Fact (Maybe).