Sparta stands out as a society singularly devoted to war and honor. Yet beneath the helmets and shields lay a complex spiritual life, deeply intertwined with the community’s social fabric and daily activities.

But who were the gods the Spartans worshipped, and what did these choices reveal about this unique city-state?

In this article, we delve into the religious practices of ancient Sparta, shedding light on the festivals, rituals, and gods that were integral to Spartan life. From Apollo, the god of military prowess, to Artemis Orthia, the goddess of birth and fertility, we explore how Spartan religious beliefs mirrored and reinforced the very ethos that made them exceptional.

spartan foundational myth

Spartans believed their lineage traced back to Zeus, affirming their unique status among Greeks. King Lacedaemon, said to be a direct son of Zeus, founded the city and married Princess Sparta.

The land was named Lacedaemon, and the city Sparta, cementing their divine origins.

A second lineage connected Spartans to the hero Heracles, also a Zeus descendant, further solidifying their divine heritage.

In comparison, Athens attributed its founding to Athena, emphasizing wisdom and democracy. The Spartan myths, focusing on divine descent, were geared towards justifying their exceptional physical abilities and warrior culture.

This made Spartans distinct from Athenians and other Greeks, aligning them more closely with physical prowess and martial skill ideals.

Lycurgus and the Oracle of Delphi

Sparta’s origin myths, centered on descent from Zeus, serve as a backdrop for the historical account of Lycurgus consulting the Oracle of Delphi. In the 9th century BC, as the need for governance grew, Lycurgus sought divine guidance from this esteemed oracle. Plutarch and Herodotus, our primary sources, confirm the divine role in shaping Spartan law.

Plutarch’s account states that Spartans would secure divine favor and establish their state by constructing temples for Zeus and Athena.

In Herodotus’s version, Lycurgus received explicit affirmation from the Oracle that Zeus chose him to create the Spartan constitution. This reinforced the city-state’s belief in its divine origin and wove it into its governing structure.

The Oracle of Delphi was a highly significant religious and cultural center in ancient Greece. Leaders often consulted it for pivotal decisions.

By seeking advice from the Oracle, Lycurgus placed Spartan governance under the auspices of divine will, intertwining mythological belief with political reality. This blend of the mythical and the historical adds another layer to understanding Sparta’s distinct identity

important spartan gods and goddesses

Spartans worshiped a broad pantheon of gods similar to the rest of ancient Greece but with localized variations. Unlike Athens, which had Athena as its patron deity, Sparta didn’t have a single city god.

However, certain gods held special significance for the Spartans.

Apollo: The God of Military Prowess and Light

Apollo was highly important to Spartans, serving dual roles in their religious practices. He was the god of war strategy, archery, and military prowess, aligning well with Sparta’s militant focus.

Apollo was also seen as a god who brought light and life, making him crucial in various Spartan festivals like the Hyakinthia, where Spartans prayed for life and victory in battle.

Artemis Orthia: The Birth Goddess

Artemis Orthia had a distinct role in Spartan religion, emphasizing her importance as a goddess of fertility and childbirth.

Spartans worshipped her at a dedicated sanctuary in Sparta, highlighting the vital role of women in Spartan society. Unlike other city-states that often marginalized women in religious ceremonies, Sparta’s focus on Artemis Orthia showed a societal recognition of women’s contributions.

Poseidon: The God of Natural Forces

Given Sparta’s geography, close to mountains and the sea, Poseidon held a unique place in their religious practices.

Known for causing earthquakes and controlling the seas, Poseidon’s worship was especially pertinent in Sparta. Rituals and sacrifices to Poseidon aimed to appease the gods and prevent natural disasters that could threaten the city-state.

While sharing many gods with the broader Greek world, Sparta’s choice of deities reflected its unique social, geographical, and military context.

spartan rituals and religious festivals

Spartans took their religious beliefs seriously, emphasizing honor and fear. Even the spirits of Laughter and Fear were worshiped, perhaps reflecting their apprehension of dishonor.

This deeply ingrained respect for the divine made religion a cornerstone of Spartan life, so much so that military commitments were often secondary to religious observances.

The Battle of Marathon: Apollo Over Athens

The Battle of Marathon fought in 490 BCE, was a pivotal moment in the Greco-Persian Wars. It pitted the Athenians against the Persian Empire and ended in a decisive victory for Athens. The win was a military triumph and a significant morale booster, proving that the Greeks could hold their own against the vast Persian forces.

Sparta’s absence from this crucial battle due to their observance of the festival of Apollo highlights the weight they placed on religious duties. The Spartans believed that the gods’ favor, especially Apollo, was essential for success in battle and life. Therefore, they opted to complete their religious festival before rushing to aid the Athenians.

Later reflections on their decision to prioritize religious observance over immediate military action were mixed. On one hand, Sparta’s focus on religious practices aligned with their deeply spiritual and militaristic culture.

On the other hand, their absence from a defining battle that helped shape Greek history raised questions about whether rigid adherence to religious practices could sometimes be detrimental to broader strategic goals.

Nevertheless, Sparta emphasized the importance of religious observances in the following years, believing that the gods’ favor was instrumental for victory and prosperity.

The Hyakinthia: A Festival of Life and Light

The Hyakinthia festival was a cornerstone of Spartan culture and religious practice, dedicated to honoring Apollo and his lover Hyacinth. Held in early summer, the festival’s three-day span was carefully structured with distinct thematic focuses each day.

The first day was typically solemn, characterized by mourning and lamentation. This was symbolic of the grief Apollo felt upon the death of Hyacinth, which according to mythology, was caused by a discus thrown by Apollo himself. The day was often filled with sacrifices and hymns to commemorate this tragic love story.

The second day shifted to a more joyful tone, celebrating the rebirth of Hyacinth as a divine being. Activities included horse races and athletic competitions, embodying Spartan physical prowess and competitiveness values.

The third day was a culmination featuring choral performances and the sharing of poems. These artistic expressions further connected the Spartans to their divine patron Apollo, who was not only a god of war but also of music and poetry.

Notably, the festival had such importance that it would halt military campaigns. Historians like Xenophon and Pausanias have cited instances where Spartans entered into truces specifically to allow for the festival’s observance.

The Gymnopaedia: A Festival of Youth and Skill

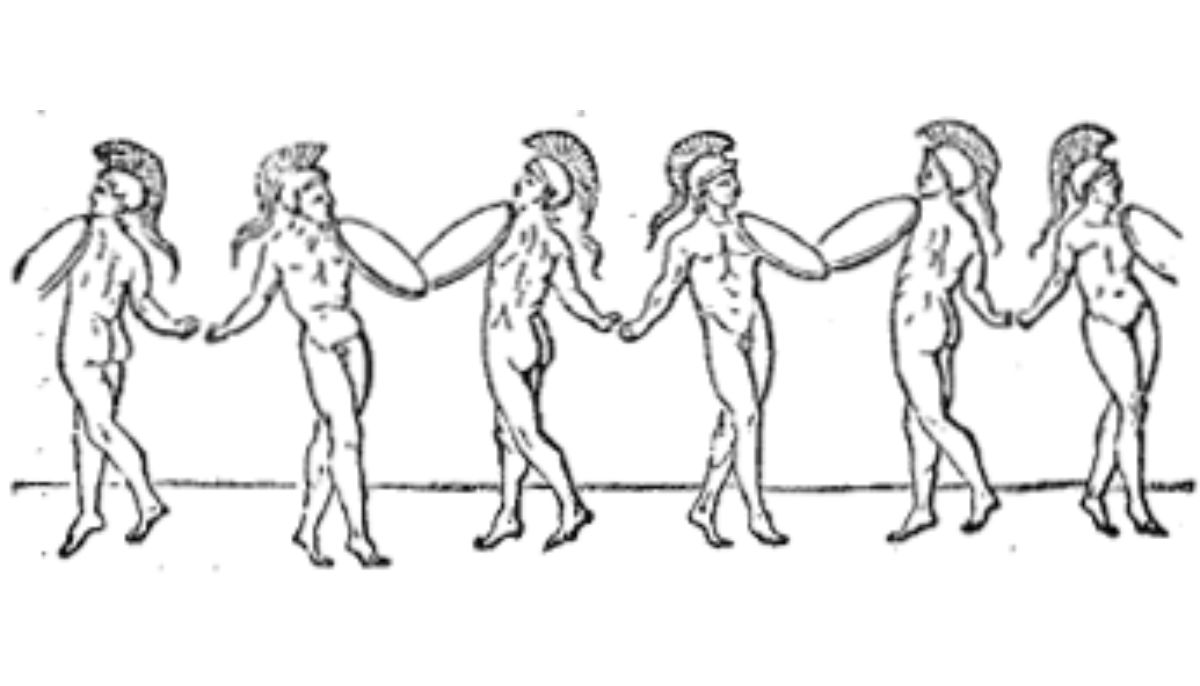

In July, the Gymnopaedia was another significant annual festival in Sparta that focused on worshipping Apollo, Artemis, and their mother Leto. Held in the city’s Agora, or public square, the event was a religious ceremony and displayed Spartan military and athletic prowess.

Choral performances at the Gymnopaedia weren’t just entertainment; they had cultural and religious significance. Dancing naked, the young men performed songs highlighting their physical maturity, a key aspect of Spartan citizenship. Songs were composed by renowned Spartan poets and carried a martial tone, linking the festival to Spartan military achievements.

These performances weren’t limited to young men. Three separate choruses—youths, men in their prime, and elders—gathered in different parts of the city to sing traditional songs.

These songs honored Apollo and depicted various life stages. In a ritual cited by Plutarch, each group sang lines emphasizing their past, present, or future strength, reinforcing Spartan unity over individual prowess.

Tests of endurance and simulated combat scenarios were part of the festival. These served as both a rite of passage for young Spartans and a test of their fitness, performed under the hot conditions of the Spartan summer.

Carneia: Apollo and the Harvest

The Carneia was a pivotal festival in ancient Sparta, held in honor of Apollo Karneios, the god of flocks, harvests, and possibly an aspect of military power. Celebrated annually from the 7th to 15th day of the Spartan month of Carneus, this festival blended agrarian, military, and piacular (expiatory) elements.

The Carneia’s piacular aspect related to the legend of Carnus, an Acarnanian seer slain on suspicion of espionage. This act led Apollo to inflict a plague on the Spartan army, which only ended after the festival’s institution. Traditionally, an animal sacrifice, possibly representing the god, was made to commemorate this event.

Five unmarried youths were selected to oversee the festivities for a four-year term, and a man garlanded with flowers would run, pursued by youths holding bunches of grapes.

If caught, this was considered an omen of good fortune for Sparta. The festival also included feasting in nine tents, each representing a different Spartan tribe, and mimicked life in a military camp, complete with commands from a herald.

Its impact on Spartan military campaigns was substantial. The Carneia was the reason for Sparta’s delayed aid at the Battle of Marathon and limited deployment at the Battle of Thermopylae. The festival was so crucial that it could halt or delay military operations, including conflicts with rival states like Argos.

The Religion of Sparta, Fusion of Belief and Practice

Spartan religious festivals were not just ceremonial but were deeply ingrained in the culture and even affected military decisions. They were comprehensive events that included solemn and festive elements, embodying the complexities of Spartan society and its respect for the divine.

It’s evident that religion was more than just a spiritual outlet for the Spartans; it was a mirror reflecting their priorities and lifestyle. This lens of religious practices also illuminates other aspects of Spartan culture, such as their rigorous military training and nuanced social hierarchies.

So, when we examine the gods they worshipped, we gain a fuller understanding of what made the Spartans truly unique in the tapestry of ancient Greek civilization.