The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC marked the end of an era in ancient history, as his vast Empire spanning from Greece to India was left without a clear successor.

This power vacuum led to intense struggle among his leading generals, the Diadochi, who vied to control Alexander’s territories.

The Diadochi, meaning “successors” in Greek, were the most influential figures in the Hellenistic world, shaping its politics and culture for centuries.

In this article, we will explore who the Diadochi were, how and why Alexander’s Empire split up, and the lasting impact the Diadochi had on the Hellenistic world.

The death of alexander the great

Alexander the Great died on June 11, 323 BC, in Babylon, a significant center of Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq. He was only 32 years old at the time of his death.

The cause of Alexander’s death is still debated among historians. Some accounts suggest that he died of natural causes, while others suggest that he was poisoned. One popular theory is that he contracted malaria, which weakened his already exhausted body, leading to his death.

Another theory is that he was poisoned by one of his political rivals, although there is little concrete evidence to support this theory.

Regardless of the cause of his death, it is clear that Alexander’s passing was unexpected and sent shockwaves throughout the ancient world.

As a military conqueror and visionary leader, he had forged a vast empire stretching from Greece to India. His death left a power vacuum that would ultimately lead to the rise of the Diadochi.

- What if Alexander the Great didn’t die?

- Could Alexander the Great have conquered Rome?

- Could Alexander the Great have conquered India?

Alexander’s famous last words on his deathbed were, “To the strongest,” when asked who should succeed him as the leader of his Empire.

These words have been interpreted as either a call to let the strongest of his generals take control or a plea to continue his vision of a united empire under a strong leader.

Regardless of their exact meaning, they symbolize Alexander’s legacy and the complex political landscape that followed his death.

Alexander’s Empire at the time of his death

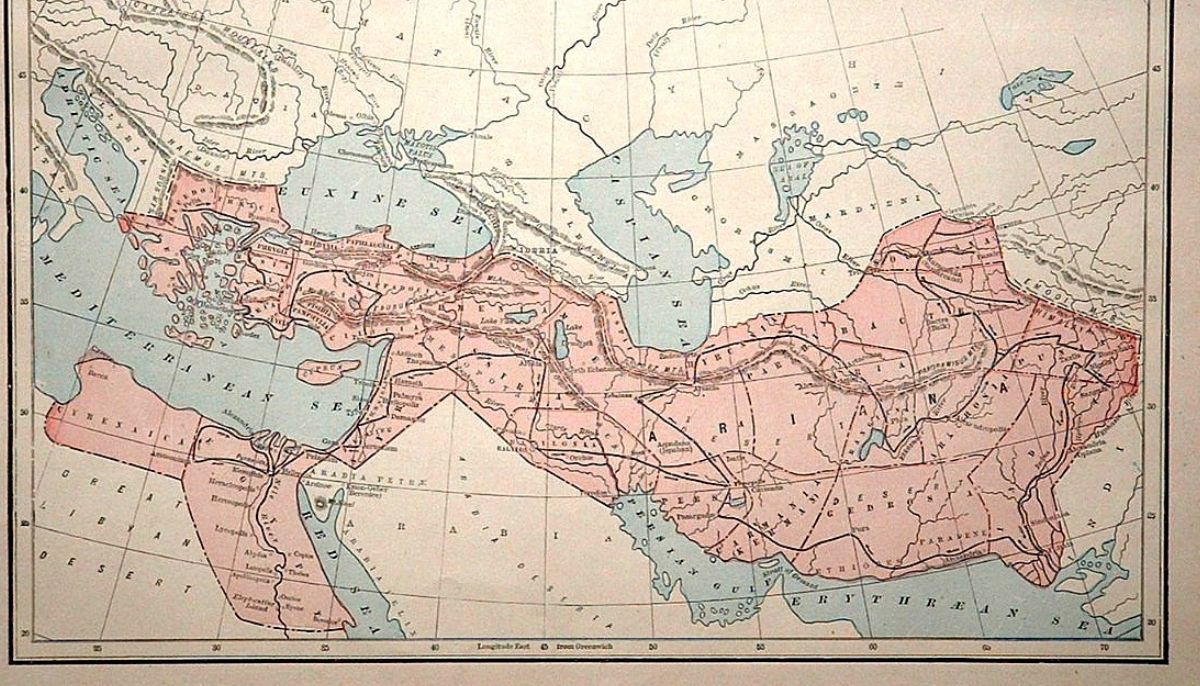

At the time of Alexander the Great’s death, his Empire was the largest in the world, spanning from Greece to India. It had taken Alexander only 12 years to conquer these vast territories.

Satrap system

The Empire was divided into provinces known as satrapies, which were governed by satraps or regional governors appointed by Alexander.

Retaining the satrap system, initially introduced by the conquered Persian Empire, facilitated a smooth transition of power. Each satrap was responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining order, and providing military support to the central government.

Under Alexander’s rule, the satrapies were divided into three regions: the Greek and Macedonian heartlands, the Persian Empire, and the newly conquered territories in Central Asia and India.

The Greek and Macedonian heartlands were the longest-held territories under Alexander’s control, dating back to the Macedonian conquest of Greece in 334 BC.

The Persian Empire had been conquered in 331 BC, and the Central Asian and Indian territories were the last to be added to the Empire, with the Indian campaign taking place in 327-325 BC.

Despite the vast size of the Empire, Alexander maintained control through a combination of military force and diplomacy. He established cities and military outposts throughout his conquered territories and encouraged cultural exchange between the Greeks and the local peoples.

Who were the generals that split up Alexander’s Empire?

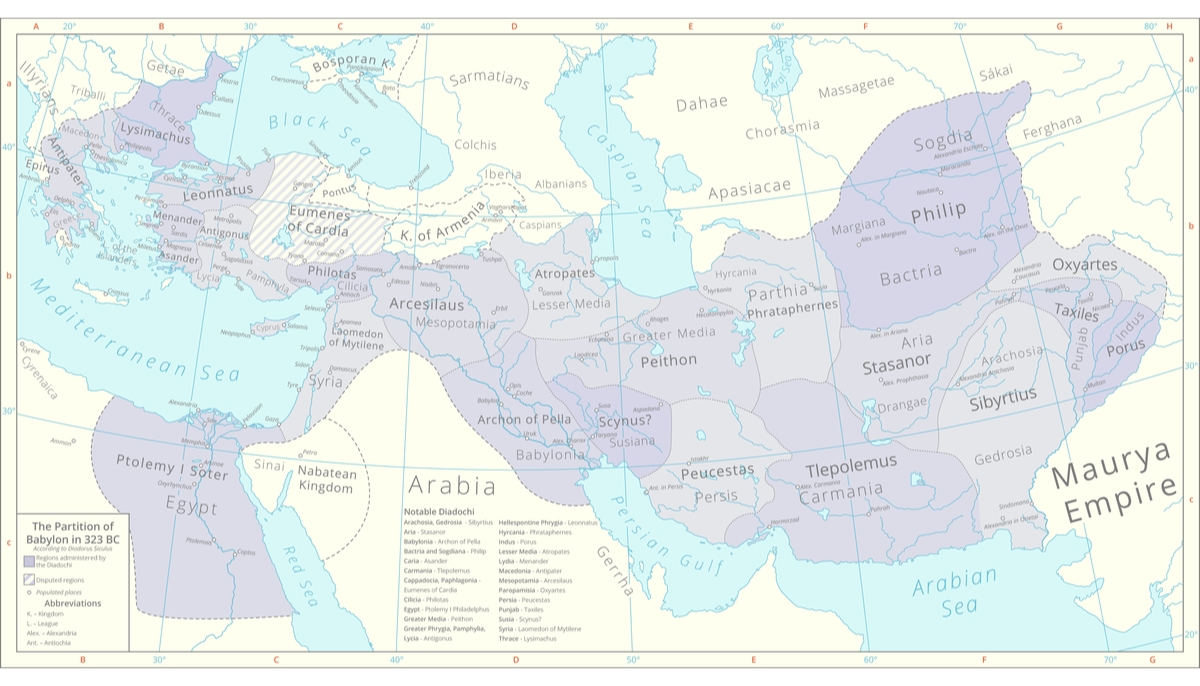

Alexander the Great’s death left a power vacuum his generals were too eager to fill, leading to decades of conflict and instability.

The Diadochi, the generals who vied for power after Alexander the Great’s death, left a complex legacy. Some founded empires that endured for centuries until the rise of the Roman Empire, while others met untimely ends in the brutal Wars of the Diadochi.

These men, whose names are etched in history, were instrumental in shaping the political landscape of the Mediterranean and the Middle East, leaving a profound impact on the world for generations to come.

Perdiccas (355-320 BC)

Perdiccas was the dominant force among Alexander the Great’s successors right after the king’s death.

His immediate power grab included taking control as regent for Alexander’s disabled half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, and his unborn son. He even aimed to marry Alexander’s sister, Cleopatra, to fortify his authority.

His rapid ascent and territorial ambitions forced other Diadochi like Ptolemy, Craterus, and Antipater into a coalition against him.

Perdiccas’ unbridled ambition was his downfall. His ill-fated invasion of Egypt to depose Ptolemy was disastrous, resulting in heavy losses.

This military blunder, combined with his lack of political cunning, led to his assassination by his generals – including the much savvier Seleucus.

In a landscape filled with strategic and cunning leaders, Perdiccas’ brute-force approach was unsustainable.

His downfall is a lesson in the limitations of raw ambition in a world that demanded a blend of military skill and political acumen.

For a Perdiccas deep dive, check out The Rise and Fall of Perdiccas – Ambition and Overconfidence.

Craterus (370-321 BC)

Craterus, a trusted general of Alexander the Great, was known for his skill as a cavalry commander. He played a crucial role in several battles, including the Battle of Issus, where he commanded the cavalry.

However, Craterus was not present in Babylon when Alexander died and was not directly involved in the initial struggles for power among the Diadochi.

He joined the anti-Perdiccas coalition in the First Diadochi War, supporting Antipater and Ptolemy in their efforts to maintain control of the Empire.

Despite his impressive military record and reputation, Craterus met an unexpected end in the Diadochi Wars. He fell in battle against one of Perdiccas’s generals, Eumenes. This surprising defeat was a blow to the coalition, as Craterus was highly respected by his fellow commanders.

Craterus’s early death prevented him from carving out his kingdom, but his legacy lived on. Want to learn more about Craterus? Check out Craterus – Alexander’s General Overshadowed by Circumstance

Antipater (400-319 BC)

Antipater was critical in securing Alexander the Great’s succession after his father’s death, King Philip II. He was entrusted with ruling Greece in Alexander’s name while the young conqueror marched east to build his Empire.

Despite his early success, Antipater eventually fell out with Alexander and his mother, Olympias.

He was later a vital member of the anti-Perdiccas coalition in the First War of the Diadochi, which sought to divide Alexander’s Empire among the generals.

After the war, Antipater was awarded the kingdom of Macedon under the Treaty of Triparadisus. He spent the rest of his life consolidating his power in the region, ultimately dying of old age at 80 years old.

To learn more about Antipater’s rocky relationship with Alexander, check out this article: The Life of Antipater – Kingmaker to Diadochi Warrior.

Cassander (355-297 BC)

Cassander was known for his ruthless methods, going to great lengths to secure his power in Macedon. He orchestrated the murders of Alexander the Great’s mother, wife, and infant son to eliminate potential rivals.

Even his father, Antipater, passed on the throne to Polyperchon, partly due to Cassander’s unabated ambition. Undeterred, Cassander ousted Polyperchon in a military coup to seize the throne.

His rule was marred by unending conflict with other Diadochi leaders, draining the resources of his kingdom.

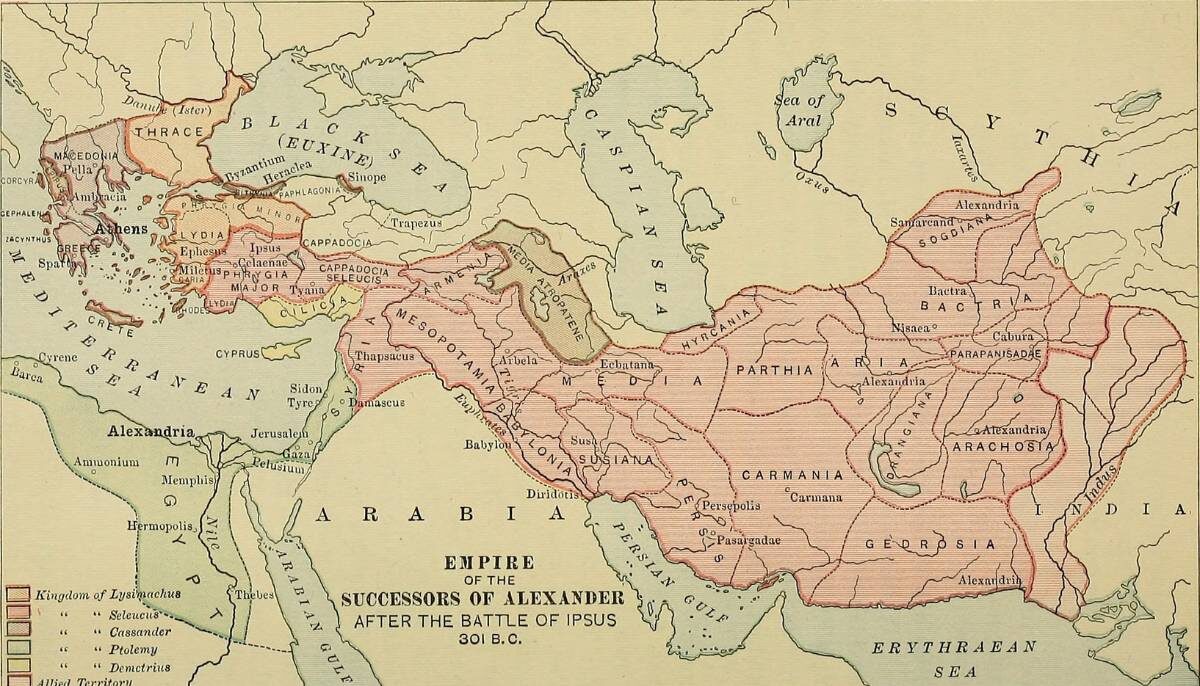

However, his position solidified temporarily after the Battle of Ipsus, where he played a role in defeating Antigonus.

Cassander’s reign was cut short by his death from dropsy, and the Empire he fought so hard to build quickly unraveled. The dynasty ended abruptly, splintered by a brutal civil war among his sons.

Lysimachus (360-281 BC)

Lysimachus was one of the most prominent of Alexander’s bodyguards, serving as one of the king’s ceremonial companions.

After Alexander’s death, he joined the anti-Perdiccas coalition, which sought to carve up Alexander’s Empire among the generals.

Lysimachus spent much time consolidating his power in Thrace, establishing himself as a ruler in his own right. He also fought in the Wars of the Diadochi, teaming up with Seleucus to defeat Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus.

Despite his initial successes, Lysimachus struggled with internal divisions later in his rule as his sons vied for power and control. He eventually fell in battle to Seleucus’ forces, ending his reign and marking the decline of the Lysimachid dynasty.

Antigonus I Monophthalamus (382-301 BC)

Antigonus, born in the same generation as Alexander’s father, Philip, rose to power after the death of Perdiccas.

Antigonus was a skilled military commander, and he quickly established himself as a force to be reckoned with in the Wars of the Diadochi. He was close to reuniting Alexander’s fractured Empire under his own rule.

Antigonus almost neutralized Seleucus before he solidified his power in the East. Similarly, in the Fourth War of the Diadochi, Antigonus nearly ousted Ptolemy from Egypt. It took a concerted effort from Lysimachus and Seleucus to finally defeat him.

In another timeline, history might remember him as the man who succeeded where others failed in piecing together Alexander’s Empire.

Although he didn’t achieve this monumental goal, Antigonus did leave a substantial legacy. He founded the Antigonid dynasty, which maintained control over Macedon and parts of Greece for over two centuries, thanks to a potent mix of military skill and diplomatic acumen.

To learn more about how close Antigonus came to ultimate victory, check out this article: Antigonus I Monophthalmus – Inches Away From Uniting Alexander’s Empire.

Ptolemy Soter (367-282 BC)

Ptolemy took a different approach from his Diadochi peers like Antigonus and Perdiccas, who aimed to control vast territories.

He wisely concentrated his efforts on Egypt, a region rich in resources and resentful of the ousted Persians.

This strategy facilitated a smooth transition of power and laid the foundation for the Ptolemaic dynasty, the longest-lasting of the Hellenistic kingdoms, enduring for over 300 years.

Politically astute, Ptolemy was open to alliances that served his interests, adding to his Empire’s longevity. Under his rule, Alexandria became a hub for culture, learning, and trade, leaving a lasting impact that still resonates in ancient history studies.

You can check out our full breakdown of Ptolemy’s role in the Wars of the Diadochi here: Ptolemy – From General to Pharoah.

Seleucus I Nicator (358-281 BC)

Starting as a minor officer when Alexander died, Seleucus rose through cunning and Machiavellian tactics to become the most remarkable political operative of his era.

He navigated the treacherous landscape of the Wars of the Diadochi with unparalleled savvy, ultimately founding the expansive Seleucid Empire.

This Empire, the largest among Alexander’s successor states, spanned from modern-day Turkey to Pakistan and endured for over two centuries.

Not just a military strategist, Seleucus was a master diplomat who formed key alliances to secure and expand his territory. He also established essential cities like Antioch, turning them into bustling centers of commerce and culture.

For those interested in learning more about Seleucus and his impact on ancient history, an in-depth article can be found at Seleucus I Nicator – Underdog To Emperor.

Legacy of the Diadochi and the Hellenistic Age

The Diadochi could hold together the vast Empire he had created for only a few years after his death.

The Hellenistic period, which followed the Diadochi era, was characterized by the emergence of these smaller kingdoms, which were ruled by different dynasties.

Spread of Greek culture

The Hellenistic kingdoms that emerged after the death of Alexander were heavily influenced by Greek culture, which was spread throughout the region by the various Greek-speaking peoples who had migrated there.

Greek language and culture became the common language and cultural currency in these kingdoms, which helped create a sense of unity among the people living there.

The Greek language became the language of trade, diplomacy, and scholarship in the eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

Art and Architecture

Significant advances in art, architecture, philosophy, and science also marked the Hellenistic period. The art of the Hellenistic period was characterized by its realism, expressiveness, and emotional depth.

Sculptures from this era often depicted the human form in motion, with intricate details and realistic facial expressions.

Architectural achievements from the Hellenistic period included the development of the Corinthian order, known for its intricate and ornate columns, and the constructing of impressive public buildings such as libraries, theaters, and gymnasiums.

Hellenistic philosophy

Philosophy during the Hellenistic period was characterized by the rise of Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Skepticism, which emphasized individual freedom, self-control, and the pursuit of knowledge.

Science and mathematics also significantly advanced during this era, particularly in astronomy, medicine, and geometry.

War and conquest of the Hellenistic states

Despite the cultural achievements of the Hellenistic period, it was also a violent and unstable time, with frequent wars and power struggles among the various kingdoms.

The conflicts between the Hellenistic kingdoms ultimately weakened them, making them vulnerable to external threats, such as the Parthians in the East and the Romans in the West.

Despite the end of the Hellenistic period with Rome’s conquest of the last Hellenistic kingdom in 30 BC, the cultural legacy of the Hellenistic period continued to be felt for centuries to come.

The poet Horace’s famous quote, “Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artes intulit agresti Latio,” captures the sentiment of many Greeks and Romans who believed that Rome was permanently changed after the conquest of Greece and the Hellenistic states.

The fracturing of the Hellenistic kingdoms ultimately allowed for the rise of mighty empires in the East and West, whose impact can still be seen today.