Welcome to an epic journey through time as we delve into the six most pivotal sieges of Constantinople!

From Byzantine resilience to Ottoman artillery, each siege brought unique tactics and dramatic outcomes.

So buckle up as we take a close look at the sieges that not only shook the foundations of Constantinople but also had far-reaching implications for empires and civilizations.

1. The 626 Sassanid Persian Siege of Constantinople: A Clash of Titans

In a time of chaos under the disastrous reign of Phocas, the Byzantine Empire found itself struggling.

Enter the Sassanid Persians, led by Khosrau II, who seized the moment to advance aggressively.

With tensions escalating, the stage was set for an epic siege that would leave a lasting impression on both empires.

The Siege

The numbers were staggering: 80,000 Sassanid troops, bolstered by a 30,000-strong vanguard, against a Byzantine force of 8,000 to 15,000.

However, numbers don’t tell the whole story. The Sassanid Persians had a strategic location across the Bosphorus from Constantinople at Chalcedon.

Despite the odds, the Byzantine navy controlled the strait, hampering the Persians from supporting their Avar allies on the European side.

Patriarch Sergius and the patrician Bonus led the defense of the city. On June 29, 626, a massive assault was launched against Constantinople’s walls.

However, a combination of high morale inside the city, encouraged by religious processions and icons, and strategic naval victories led to the siege’s failure.

The Aftermath

After the siege, things took a dramatic turn. A Byzantine fleet destroyed a raft of Persian troops on the Bosphorus, and Avar and Slavic allies faced a similar fate.

The news of victories elsewhere weakened the resolve of the invaders, leading to their retreat. As a result, the Sassanid general Shahrbaraz even switched sides to join Heraclius.

The Far-reaching Effects

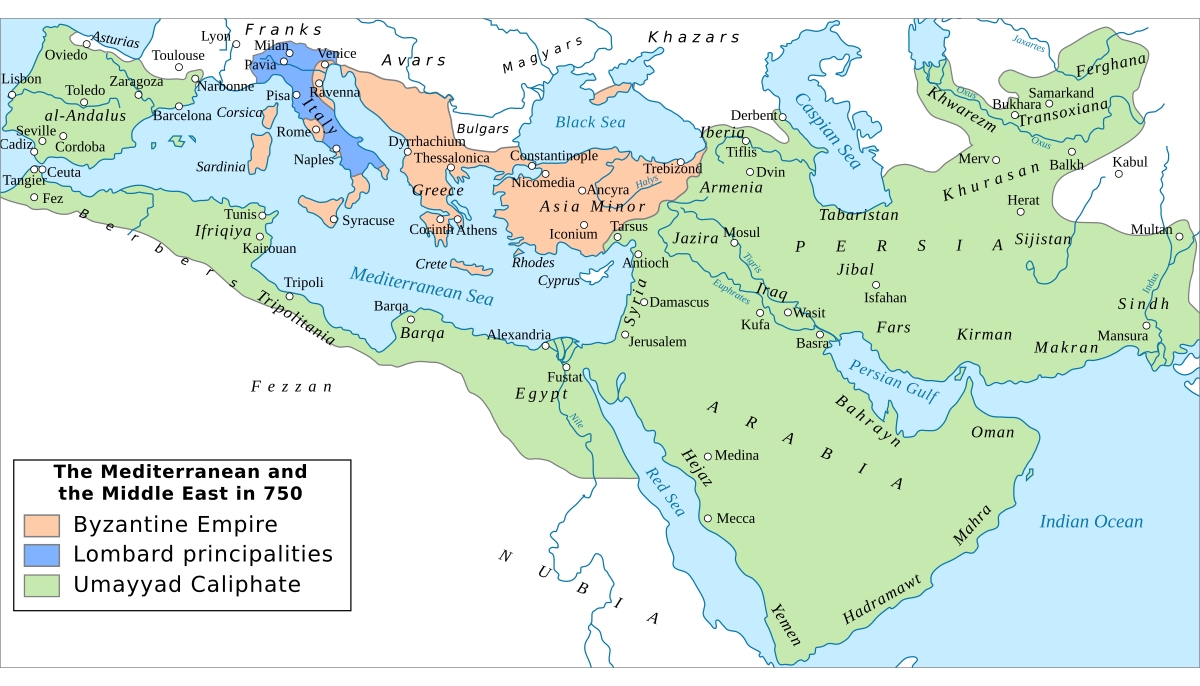

This was not a victory without cost. The war severely weakened both empires. The Byzantines and Persians would never be the same, opening a pathway for a new power— the Arabs.

The siege of 626 can be seen as a catalyst, signaling the decline of both empires and setting the stage for the Arab-Islamic invasions that would follow.

2. 674-678 Umayyad Siege of Constantinople: A Pivotal Moment in Arab-Byzantine Wars

The 674-678 Umayyad siege of Constantinople was an ambitious undertaking by the Umayyad Caliphate under Caliph Mu’awiya I.

The siege aimed to capture Constantinople, the heart of the Byzantine Empire. It was a protracted conflict marked by constant skirmishes and sieges, mostly in the Sea of Marmara region.

Strategy and Engagement

The Arab fleet would arrive each spring to assault the Byzantine capital, retreating to Cyzicus during winter.

Despite the intensity, the siege was not a continuous encirclement but a series of engagements over several years. It was a grinding process for both the Byzantine and Arab forces, with battles ranging from the Golden Gate to the Kyklobion area of the city.

Use of Greek Fire

In the final battle of the 674-678 Umayyad siege, the Arab forces, which had numbered around 200,000 men for the full siege, faced off against the Byzantine fleet. The Byzantines had a game-changing weapon: Greek fire.

The Byzantines utilized Greek fire to inflict significant damage on the Arab fleet. The Arab forces reported about 100,000 casualties throughout the siege, a staggering number that contributed to their ultimate withdrawal.

The Byzantine’s strategic use of Greek fire was pivotal in defending Constantinople, effectively halting the Umayyad Caliphate’s expansionist ambitions. The high casualty rate among the Arab forces underscored the weapon’s devastating impact, changing the course of the siege and, by extension, the Arab-Byzantine conflict.

Aftermath

While the Byzantines were focused on the Arab threat, they lost ground in Italy to the Lombards and faced Slavic raids in the Balkans. Their stretched resources were evident, but the importance of defending Constantinople took precedence.

The siege ultimately failed, resulting in a significant loss of resources and prestige for the Umayyad Caliphate. For the Byzantine Empire, the victory bolstered its prestige and provided a respite from constant raids, especially in Asia Minor. The siege’s failure led to negotiations and a truce that lasted for several years.

Had Constantinople fallen, the Byzantine Empire would have likely disintegrated, making it easy prey for Arab expansion.

3. 717-718 Umayyad Siege of Constantinople

After the first Arab siege of Constantinople, the Umayyad Caliphate was focused on internal conflicts, giving Byzantium some breathing room.

However, when the Umayyads stabilized, they were back with a vengeance. The Byzantines were losing grip on their territories, and the Arabs saw another chance at Constantinople.

Caliph Sulayman, motivated by what he believed was divine prophecy, amassed an army and fleet reported to number around 120,000 men and 1,800 ships.

The Siege

The Umayyad forces arrived in the summer of 717, besieging Constantinople from land and sea.

Despite the grand scale and initial successes, the siege turned sour for the Umayyads. The Byzantines deployed their best weapon – Greek fire. The arab fleet was decimated.

Winter came along, turning the Arab camp into a house of horrors. Food ran out, and diseases ran rampant. To make matters worse, new Arab fleets, sent as reinforcements, were decimated by the Byzantines.

Aftermath and Effects

The failed siege was more than a military blunder for the Arabs; it was a devastating financial and political blow. The Umayyad Caliphate found itself reconsidering its aggressive territorial ambitions.

For the Byzantines, a hard-fought victory fortified their capital and boosted morale.

The siege of 717-718 didn’t just fail to capture a city; it shifted the balance of power and set the stage for the ebbs and flows of Byzantine-Arab relations for years to come.

4. 1203 Fourth Crusades siege of Constantinople

The Fourth Crusade began with the intention of conquering Muslim-held Egypt. However, financial struggles led the Crusaders into massive debt with Venice.

In an unexpected turn, Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos offered financial and military support for the Crusade, with a catch: first, they had to help him reclaim his throne in Constantinople.

Agreeing to the deal, the Crusaders arrived at Constantinople on June 23, 1203.

The Siege Itself

To take the city, the Crusaders had to cross the Bosphorus Strait. Utilizing a fleet of 200 ships, they faced off against Byzantine forces led by Alexios III.

The Byzantines retreated, allowing the Crusaders to lay siege to the Tower of Galata. After heavy fighting, they gained control of the Golden Horn, allowing the Venetian fleet to enter.

The Crusaders took their positions opposite the Blachernae palace on July 11. Despite parading Alexios IV outside the walls, the citizens remained unswayed, showing loyalty to Alexios III.

On July 17, the real action began. The Crusaders split into four divisions to assault the land walls, while the Venetian fleet targeted the sea walls from the Golden Horn. Remarkably, the Venetians captured a section comprising about 25 towers.

Meanwhile, the Varangian Guard, an elite unit of the Byzantine Army, put up staunch resistance on the land walls. They eventually shifted their focus to the new threat presented by the Venetians, who then pulled back under cover of fire.

This fire escalated, lasting for three days and destroying approximately 440 acres of the city.

Alexios III led 17 divisions from the St. Romanus Gate to confront the Crusaders. With about 8,500 men, his army vastly outnumbered the Crusaders’ 3,500.

Yet, inexplicably, Alexios III retreated without engaging in combat.

The defining moment came on July 18 when the Crusaders launched another assault. Alexios III fled the city, leaving it leaderless.

The following day, the Crusaders discovered that the citizens had freed Isaac II from prison and re-established him as Emperor. To bring the siege to a close, the Crusaders pressured Isaac II to make his son Alexios IV co-emperor on August 1.

Aftermath

The Crusaders’ immediate objective was complete; Isaac II was restored, and his son Alexios IV was made co-emperor.

However, the political atmosphere was volatile. Alexios IV now faced the Herculean task of fulfilling his grand promises to the Crusaders, which seemed increasingly impossible.

The city was vulnerable, and the Crusaders were frustrated and still in debt. All these elements contributed to the tension that would culminate in the infamous sack of Constantinople in 1204.

5. 1204 Crusader sack of Constantinople

Tensions reached a boiling point between the Crusaders and the Byzantine Empire. Initially, Alexios IV aimed to bring stability to the capital but only inflamed hostilities.

City-wide riots between anti-Crusader Greeks and pro-Crusader Latins broke out until November.

The Byzantine public turned increasingly against Alexios IV. His downfall came swiftly; he was deposed, imprisoned, and executed in early 1204.

His successor, Alexios V, tried but failed to negotiate the Crusaders’ withdrawal, further escalating the impending clash.

The Siege and Sack

The Crusaders and Venetians launched their first siege attempt on April 9, 1204, but were met with fierce resistance and had to retreat.

By April 12, favorable weather conditions offered a second chance, enabling them to cross the Golden Horn and successfully breach the city walls.

Once inside, the Crusaders unleashed three days of chaos and destruction. Iconic artworks were either stolen or melted down for their raw material. Churches and holy sanctuaries were not spared; they were looted for gold and marble.

The human cost was also high, with an estimated 2,000 Byzantine civilians losing their lives.

The Aftermath

Following the sack, the Latin Empire of Constantinople was established. Boniface of Montferrat, initially considered for the imperial crown, was overlooked due to his connections with the Byzantine elite.

Instead, Baldwin of Flanders was crowned the new Emperor. The Byzantine aristocracy fled the city, with some establishing successor states like the Empire of Nicaea.

The event drastically weakened the Byzantine Empire, setting it on a path that would eventually collapse in 1453.

6. 1453 Ottoman Siege of Constantinople

By 1453, the Byzantine Empire was a shadow of its former self. Plagued by internal strife, economic decline, and the aftermath of the Black Death, it had shrunk considerably.

The capital, Constantinople, was more like a patchwork of walled villages than a bustling metropolis. Defending it was a small, under-equipped force led by Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos.

The ambitious 21-year-old Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II, opposed him, eager to seize the city and make it the new Ottoman capital. His army was vast, estimated between 50,000 to 80,000, including the elite Janissaries and an artillery corps.

The Siege and Fall

Mehmed II’s game-changing weapon was the cannon. Developed by Orban, a Hungarian engineer, the largest among these could hurl a 600-pound stone ball over a mile.

Despite their long reload times and imprecision, they breached walls that had stood for centuries. Byzantine attempts to repair the damage mainly were in vain.

On May 29, after a multi-layered assault, the Ottoman troops penetrated the city’s defenses. Constantine XI led a desperate final charge but was overwhelmed. The city’s defense crumbled when Turkish flags were seen atop the walls.

The Aftermath

The fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, effectively concluding a lineage tracing back to the Roman Empire.

Mehmed II rode into the city and, in a symbolic act, converted the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. The event also marked a turning point in military history, showcasing the might of artillery. Mehmed II earned his nickname “The Conqueror,” the Ottomans now controlled the crossroads between Europe and Asia.

For the first time since the invention of Greek fire had halted Arab sieges centuries before, a new superweapon had definitively changed the course of history in the region.

Constantinople faced multiple sieges throughout its history, each shaping its destiny uniquely.

From the Arab sieges deterred by Greek fire to the Fourth Crusaders’ unexpected sack, and finally, to the Ottoman conquest that deployed groundbreaking cannons, the city was a stage for evolving military tactics and geopolitical shifts.

Constantinople’s resilience and eventual downfall offer lessons on the impermanence of empires and the transformative power of technology.

Would it still be the bridge between two worlds?

Each siege leaves us with tantalizing “what ifs,” underscoring the city’s enduring impact on world history.